Matthew Barney's seven-hour Cremaster Cycle descends in the Portland Museum of Art

By ANNIE LARMON | November 10, 2010

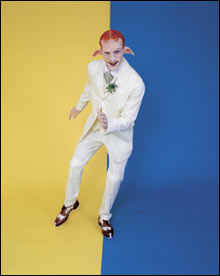

CREMASTER 4 |

Eight years after its completion, The Cremaster Cycle, Matthew Barney's interminable multi-media opus, continues to befuddle and intrigue audiences. In a marathon cinematic experience that virtually eschews narrative and dialogue, Barney concocts an insular parallel world bred from autobiography, biological allusion, mythology, and conspiracy theory. In 1994, the sculptor and performance artist set out to complete an earthwork, or land sculpture, on the Isle of Man. The sculpture organically developed into Cremaster 4, the film that is now the fourth in a series of five, as Barney played with the introduction of action to the object. Cinema became the format for his eight-year globe-spanning investigation into gender, metamorphosis, masculine identity, and regression.Barney, who was deemed "the most important American artist of his generation" by the New York Times Magazine, is a controversial figure in the art world. While Cremaster maintains a cult status, perhaps aided by the film's unavailability, his work has had an equivocal reception by critics, who have a difficult time allying the artist with either avant-garde cinema or fine art camps. His notoriety is superficially bolstered by his status as Bjork's groom and his quirky star-athlete-turned-conceptual-performance-artist story, never mind his Roman physique. The integrity and originality of his media-bending performance survived a stint of Barney as art star media darling, however, and Cremaster deserves to be seen by any art- or cinephile who has the endurance to sit through all 400 minutes of it.

The cremaster, of course, is the muscle that raises and lowers the scrotum in order to protect and regulate the temperature of the testes. The Cycle chronicles the process of the ascended reproductive organs to a state of descension during embryonic sexual differentiation. The state of undifferentiation represents "potentiality" in the films, a trope that lends the entire series an air of suspension, a confusion that, like the creative process, never finds resolve. Thematically, the cremaster serves as a point of departure for the artist to tackle any variety of reproductive processes that involve in-and-out or up-and-down actions. On the performance front, expect to see a lot of climbing and falling. Sculpturally, get ready for uncomfortable amounts of Vaseline, tapioca pearls, and anything that happens to be sticky and white. The forms of a slew of absurd non-gendered prosthetic genitals become motifs that thread through the films.Loosely clinging to an esoteric collection of references and mythologies, Barney's aesthetically riveting pageant unravels into a series of harshly edited pseudo-narratives that address the arbitrariness of human ritual, symbolism, and identity. Comparing the human life to that of a drone bee and reducing our intention to the will of nature, Barney both approbates and undermines the material culture we decorate ourselves with. Barney confronts the moment of differentiation with his parallel fantasy world full of opulently costumed real and exaggerated human bodies, mocked misogyny, and gender contortionists. There are countless up-the-skirt shots and we are confronted with testicles so often they become as innocuous as potatoes, or grapes.Barney's metaphors can be frustrating, as they are either briefly introduced and whisked away before we are able to grasp their intention, or driven home so intensely by repetition and redundancy that we begin to lose interest. That said, at least when ingesting the work in its epic totality, it seems a dose of monotony here and there is necessary to fully enter Barney's world, by submitting to a dream or drug state. The overall effect of these films is stunning, in both senses of the word, and might be compared, at best, to reading diluted Pynchon. Convoluted as they are, the moments in the films where logic is suspended are where Barney is at his best. It is probably best to give in to the experience and save the interpreting for later.

Related

Related:

Grace Zabriskie on Big Love and marriage, Review: Red Cliff, Review: The Strip, More

- Grace Zabriskie on Big Love and marriage

Through the course of 80 films and countless television guest spots, actress Grace Zabriskie has worked with directors as varied as David Lynch, Werner Herzog, and Michael Bay.

- Review: Red Cliff

Hong Kong auteur John Woo hit commercial and artistic pay dirt in the US with Face/Off , his loopy Nicolas Cage/John Travolta neo-noir, but once he’d directed Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible II , was there anywhere left to go?

- Review: The Strip

In lieu of Steve Carell’s hopelessly inept and earnest manager, we have his creepier duplicate, Glenn. Instead of the boorish brown-noser played by Rainn Wilson, there’s the more obnoxious Rick.

- Review: A Single Man

Christopher Isherwood published his novel about a middle-aged homosexual grieving for a lost lover, the frank depiction of gay desire scandalized some readers.

- Review: Shutter Island

I read Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island , a 336-page throat-grabbing mystery thriller, in two nearly sleepless nights.

- Review: Meredith Monk: Inner Voice

After studying music and dance at Sarah Lawrence College in the '60s, Meredith Monk was struck by the idea that the voice could be like the body — it could move, it could have characters and landscapes, it could alter time.

- Review: Neil Young Trunk Show

If a Neil Young neophyte can find himself rocking in a cinema seat to the spirited, soulful music performed in this second of a rumored triptych of Demme-directed, Young-starring concert documentaries, long-time fans are bound to break their armrests.

- Review: A Matter Of Size

Director duo Sharon Maymon and Erez Tadmor have fashioned a look at a group of blue-collar Israeli men and how they came to accept who they are.

- Review: Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies

Picasso seems to have done so, though preferring Chaplin slapstick and cowboy silents to artsy fare, and biographers place him at several screenings of Lumière shorts.

- Review: Win Win

Back in the '30s, with directors like Frank Capra and John Ford, Hollywood showed great sympathy for the forgotten men and women laid low by the economy.

- Review: Limitless

Neil Burger ( The Illusionist , The Lucky Ones ) hasn't previously displayed much of a personal style, but here he opens with street-level power-of-ten shots, his camera zooming forward, through people and vehicles alike.

- Less

Topics

Topics:

News Features

, Johnny Cash, metaphor, Morbid Angel, More  , Johnny Cash, metaphor, Morbid Angel, Religion, Movies, Norman Mailer, Dave Lombardo, Richard Serra, Prison, Matthew Barney, Less

, Johnny Cash, metaphor, Morbid Angel, Religion, Movies, Norman Mailer, Dave Lombardo, Richard Serra, Prison, Matthew Barney, Less