DUO CONCERTANT I: Louise Nadeau and Olivier Wevers had the body language but not the facial expression. |

All summer long I’ve had the phrase “Do the Lambarena” running through my head, as if it were a dance craze, like the la-dee-dah or the lambada. It’s actually a suite of pieces assembled by Pierre Akendengué and Hughes de Courson that, taking its name from the town in Gabon where Albert Schweitzer founded a hospital in 1913, fuses Schweitzer’s beloved Bach — but why so many Passion selections? — with West African rhythms. In 1995, Val Caniparoli drew on that score to create for San Francisco Ballet a dance of the same name, in which men hunt, women carry, and there’s a Crucifixion scene to the Agnus Dei from the B-minor Mass. Boston Ballet staged it last March: the Times’ John Rockwell liked it, the Boston critics didn’t, audiences were divided as to whether it was an authentic African experience or just a tourist visit.I wondered what Caniparoli’s work would look like on a less white company — specifically Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. It was, however, Pacific Northwest Ballet, under new director (and former New York City Ballet principal) Peter Boal, that brought Lambarena to Jacob’s Pillow last week, and it turned out that PNB is even whiter, an entire company of Karine Senecas, the Boston Ballet principal who in the lead female role conjured a white woman in Africa not trying to be anything else. Seneca at least had some elegance; PNB’s Ariana Lallone was stiff-bodied, only her arms and her head in any kind of locomotion, and in his solo Olivier Wevers could have been auditioning for a Jan & Dean video. Clarisse Mouassi’s singing of the opening “Sankanda” is so kinetic that the absence of swivelhips on stage can’t spoil it, and the combination of “Ruht wohl ihr heiligen Gebeine” (from the St. John Passion) with handclaps and a precentor’s invocations to the dead and the living and some disquieting animal movement from Caniparoli is hard to shake. Lambarena also looked less ambitious, and less pretentious, on the smaller Pillow stage than it did at the Wang Theatre. But it still has “Whiteboy visits Africa with Berlitz and Baedeker” written all over it.

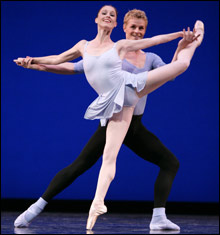

Pacific Northwest Ballet also brought company ballet master Paul Gibson’s The Piano Dance, PNB choreographers’-showcase contributor Sonia Dawson’s Ripple Mechanics, and George Balanchine’s Duo Concertant. This last, choreographed for NYCB’s 1972 Stravinsky Festival to a duo for violin and piano that Igor composed in 1932, puts the musicians downstage right and has the two dancers stand alongside and listen to the first section, Balanchine’s way of saying that it all starts with the music. Marjorie Kransberg-Talvi’s violin sounded a little muddy; Louise Nadeau and Olivier Wevers, meanwhile, looked on with frozen smiles straight out of The Lawrence Welk Show, and when they started dancing, they kept grinning at the audience and hardly looked at each other, as if to say, “No sex, please, we’re . . . Balanchine dancers?” Hard to believe that Boal, who was not only a principal at NYCB but a very good one, doesn’t know better. And such a waste: Nadeau from the neck down was exemplary, at once available and unavailable, her pelvis saying yes as her eyes said no, and Wevers had everything except an intelligent expression.

The Piano Dance is a neo-Balanchine work — think Rubies with less engaging music (Chopin, Cage, Ligeti, Bartók, Ginastera) and pointlessly funky costumes (red leotards with short tail skirts for the ladies, red trousers with one leg bare and the other sporting three orange hoops for the men). The only music I recognized was Chopin’s E-minor Prélude (lugubriously played by Dianne Chilgren), which Gibson decorated with dreamy développés, as if stretching before (or after) sex. There were also some flashy original moves — Louise Nadeau thrust upside down and held in sexual suspension — in the ninth of the 10 pieces. But so much of it looked like a Rubies homage (with perhaps a nod at The Four Temperaments) that I wondered why they didn’t just do the real thing. It’s not as if Boal didn’t have good dancers.

Ripple Movements, for one woman, three men, and four cubes for sitting, had still funkier costumes — red with black and yellow accents — and more negligible music, Jacqueline Fuentes singing “Sinuoso trópico,” Nina Simone doing “Ne me quitte pas.” The press material promised “a modern dance æsthetic” in which the dancers would explore Dawson’s “idea of how neutrons and electrons interact.” Real neutrons and electrons would have been more interesting.