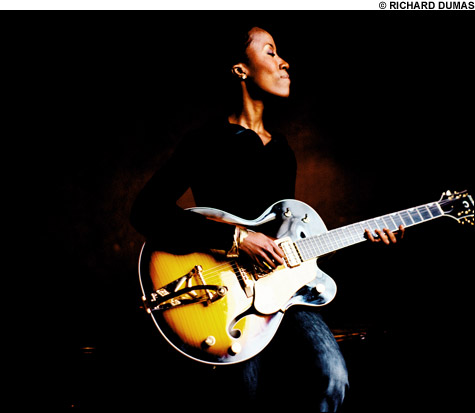

SOFT FOCUS: "It's not a question of lacking power. I can sing with power. What I'm interested in is depth." |

Some albums are extraordinary because they capture their time. Others are great because they transcend it.

Malian performer Rokia Traoré's arresting new Tchamantché (Lamá/Nonesuch) is one of the latter. With its mix of ancient tradition and modernism, soft, pleasing sounds, and a precision in tone, taste, and timing that extends even to the sigh of her breath as her vocal phrases resolve, Tchamantché arrives as a classic whose influence may ultimately extend beyond the realm of African recordings.

"I'm not trying to do anything unusual with my music," Traoré, whom World Music is bringing to the Somerville Theatre this Friday, modestly insists by phone from Paris. "My music is me."

Yet this latest album's innovations are obvious. Foremost, the disc is propelled by the butterfly flights of her vocal melodies, not rhythms. Drums make only cameo appearances. And the blend of her guitar playing — angular, dry, and unpredictable as American avant-roots hot-shot Marc Ribot's — with the distinctly African balafon and ngoni is striking.

Like Miles Davis's epochal Kind of Blue, which debuted 50 years ago, Tchamantché is elegant and graceful in an almost elemental way. And like Davis's trumpet, Traoré's voice speaks a beautiful universal language. So it doesn't matter that she sings nine of the album's 10 songs of desire, acceptance, longing, and protest in French and Bambara.

Another parallel with Kind of Blue–era Miles is that Traoré already had achieved artistic acclaim for playing a more traditional style of music before making this entrancing album. The 35-year-old diplomat's daughter won the prestigious Radio France Internationale African Discovery prize in 1997 for an approach closer to that of her guitar mentor, Ali Farka Touré. That was a year before her debut, Mouneïssa (Indigo France), was released.

After that, her music blossomed. By 2003 and Bowmboï (Nonesuch), she was collaborating with the Kronos Quartet. Then she was working with Western rhythm sections. In 2006 she wrote a work for Vienna's New Crowned Hope Festival under the artistic direction of the auteur Peter Sellars that cast Mozart as a 13th-century griot.

"Blues, classical, rock and roll, jazz, funk, pop — all these are part of me," she relates. "I started listening to all kinds of music in my father's collection when I was five. He played albums for me because I was his child who was instantly interested in music."

Yet her father later opposed her decision to become a musician, fearing she'd be doomed to poverty in a profession dominated by arrogant males. "I never felt I would fail. I told him if I needed money I could always be a housekeeper, but if I hadn't decided to become a musician, I might have been an architect or a teacher. As things have occurred, now my father is very proud."

Certainly she is an exceptional student. It's not surprising that Traoré considers Miles Davis an important influence, along with Billie Holiday, whose "The Man I Love" she sings in English on Tchamantché. Salif Keita, Ella Fitzgerald, and Louis Armstrong are on her short list, as well as female Malian singers like Oumou Sangaré. She even performed in an American-style hip-hop band before launching her solo career.

"One thing I learned listening to all of that music and working with other musicians, especially Ali [Farka Touré], was the importance of space." The distance between Tchamantché's slow-flowing sculpted notes is an important contributor to its élan, and another quality it shares with Kind of Blue, and the late Touré's masterpieces, among them his famed collaboration with Ry Cooder, Talking Timbuktu (Hannibal).

"Silence and repetition are crucial," Traoré continues. "Sometimes in my lyrics I use only several words. The emotional essence of my songs is very important, and using the same words or surrounding notes by silence intensifies things."

On Tchamantché she wrestles with issues of death and faith ("Dianfa"), and she protests Mali's high level of expatriation to France and Spain ("Tounka"). "Our richness only brings us wars and slaughter/famine and diseases," she sings in Bambara.

But it's not all pointed and pained songs. The beatific "Zen" celebrates, in her words, "the courage to do nothing," to live in the moment. "Dounia" praises heroes of Africa's past even as it frets over the continent's present.

"Everything in life is hard to accomplish," she observes. So far her greatest accomplishment is a style of artistic expression every bit as singular as Tom Waits's, albeit prettier by far. "I learned to play guitar by myself starting 10 years ago, so I made up my own tunings. By the time I bought lesson books and learned about standard tuning, I was already playing in my particular way. Today I use common tunings, but I also use my own tunings to get what I want from the instrument" — usually an old Gretsch or Silvertone, the kind of six-string she first heard on American blues and rock recordings.