|

You've got a beautiful, possibly bi-sexual woman who'll stop at nothing to get what she wants. (She's already ditched two husbands.) You've got an effeminate, possibly mad ruler who's what she wants. You've got a crotchety philosopher and conscience whom the effeminate ruler orders to commit suicide. Government comes to a standstill, and discarded lovers are everywhere, along with plots against the throne. It might sound like something out of the pages of your favorite supermarket tabloid, but actually it's Claudio Monteverdi's 367-year-old opera L'incoronazione di Poppea, or The Coronation of Poppea, the (mostly) true story of what Roman emperor Nero did for love, as he divorced his wife, Octavia, to marry Poppea. Monteverdi's masterpiece — the first surviving political opera, and surely the first with an ironic ending — is the centerpiece of next month's 15th biennial Boston Early Music Festival (which is being called "The Power of Love"!), in six fully staged performances at the BCA's Calderwood Pavilion. It'll be helmed by BEMF artistic co-directors Paul O'Dette and Stephen Stubbs, with Gillian Keith as Poppea and Marcus Ullmann as Nero.

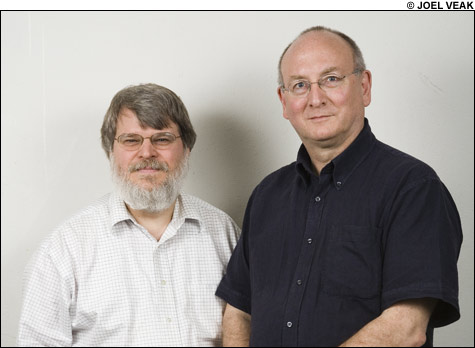

Many operas have gorgeous music and a silly story; Poppea has gorgeous music and a sobering story. Here's some of what O'Dette and Stubbs had to say about it.

Could you talk about Poppea as the first political opera? And about why it's still relevant in 2009?

O’Dette: Poppea seems to be the first historical opera, that is, a work based on actual historical figures as opposed to characters from mythological or other classical sources, usually Ovid or Homer. It seems to have been written as part of a trilogy of operas Monteverdi composed in 1640, 1641 and 1642. The political message of these three seems to have been to reinforce the then new idea of a Venetian genealogy in which the first one, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria [“The Return Home of Ulysses”] presents the fall of Troy, the second, Le nozze d’Enea e di Lavinia [“The Marriage of Aeneas and Lavinia”], represents the founding of Rome, and the final part, Poppea, shows the decadence and eventual fall of Rome, leading to the rise of Venice as the new center of civilization and culture. This notion of Venice as the empire that took over from Rome is also presented in other Venetian operas and books of the mid 17th century. Opera fans have often puzzled over the fact that Poppea does not appear to have a character the audience wants to root for, since everyone has seriously objectionable traits. But since the Venetian audience was expected to read the opera as presenting the decay of the Roman Empire, these character flaws were meant to strengthen that perception.

Poppea is still relevant today because it is a dramatic work of exceptional power, set to music of extraordinary beauty, variety, and impact. It is unquestionably one of the very greatest pieces of musical theater ever written, a work that speaks to us as powerfully and directly today as it did to the audiences of the 17th century.