All eight numbers on Nuevo Ballet Español’s “Flamenco Directo” program seemed to end with a surge of noise and energy, a thrust into a rakish pose, a long pause to invite the audience’s screams, and a coda in which the dancer took a nonchalant exit. You’ll see this trope on most any flamenco concert. Nuevo Ballet Español uses it as an automatic crowd ripper. The ploy can lose its effect unless it’s gunned higher with each repeat. Eventually, nothing matters but the screams.

World Music cooked up a big contrast with this year’s Flamenco Festival at the Cutler Majestic by pairing Nuevo Ballet Español with Noche Flamenca. Both companies claim to be doing traditional flamenco, but Nuevo is a would-be Riverdance entertainment whereas Noche offers only the gifted individuality of its interpreters. One outfit asks us to probe into the heart of the art. The other shows us the art’s outlines and assumes we don’t want to be taken to the depths.

Noche Flamenca, returning to Boston after more than two years, surrounds its prima, Soledad Barrio, with an ever-changing ensemble. This time Barrio and Isabel Bayón were joined by two male dancers, Antonio Rodríguez Jiménez “El Cupete” and Juan Ogalla, singers Manuel Gago and Antonio Campos, and guitarists Jesús Torres and Eugenio Iglesias. The show is very straightforward, a recital, really, of what these artists of different temperaments and talents can tell us.

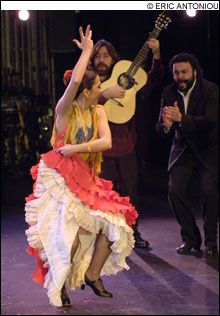

The evening is orchestrated like a series of acts in a taverna; the mood is somber, the lighting is dim, and each performer holds forth with a personal outcry of dance and music. The rhythms, with embellishments and variations, tell of their pain and passion even when you can’t translate the words. Some of these survivors emote, spilling over the top with intensity; some of them are more contained. All of them are masters of step and gesture.

The Nuevo Ballet Español dancers exploit the visual pleasures of sinuous bodies, rflamboyant arms, and snaky hands. The nine dancers use an eclectic vocabulary in addition to the flamenco body shapes: stamping and vibrating foot articulation, balletic spins, modern dance stretches and twists, mime and histrionics.

This production’s approach is that of a rock concert. The musicians, highly amplified, sit lined up on a platform at the back. The star dancers, company directors/choreographers Ángel Rojas and Carlos Rodríguez, do many solos and duets. The others are arranged in ensembles for basic group patterns: diagonals, chorus lines, accompanying frames for solo bits by one of their members.

The usual guitars are complemented by a flute, a cello, and a percussionist — congas, frame drum, cymbals. Antonio Blanco’s music sometimes sounds traditional, but it’s often a fusion of Afro-Latino-rock populism. The dancers seem to replicate the loudly miked underpinnings of drummer Diego Álvarez “El Negro,” so even though the floor is miked too, you can’t really make out what the dancers’ rhythms are. They could be faking it, but the audience wouldn’t care.

It’s the look of flamenco that these dancers exploit. The group slam into unison stepping routines. Couples carry on tense courtships and wrap into steamy embraces. Rojas and Rodríguez both have solos, and they duet like brotherly rivals.