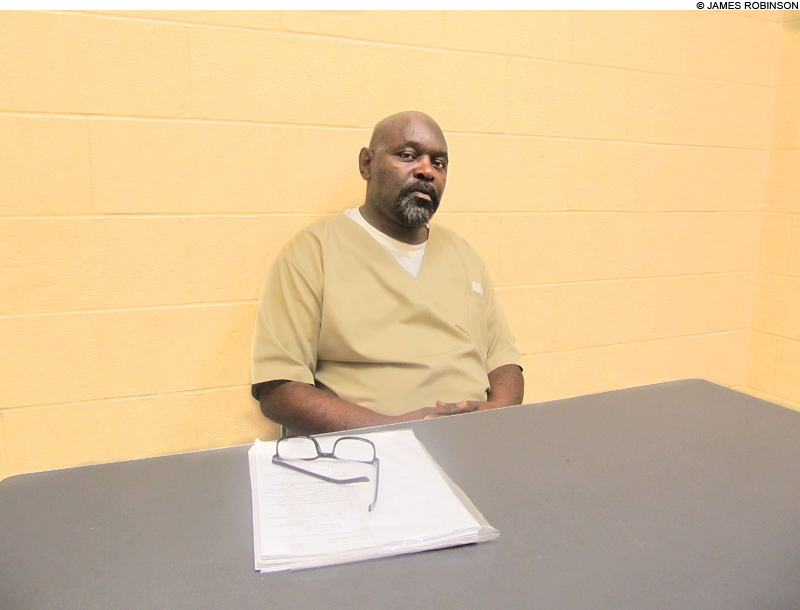

JAILED Spivey at the Adult Correctional Institutions. |

The young woman, just 18 years old, was standing at the driver's side door of her blue Volkswagen in the parking lot of St. Joseph's Hospital in Providence on a clear and wintry Saturday evening when a young black man approached from behind and put a knife to her throat. This section of the parking lot was in darkness at night, unnamed hospital employees would grumble to the Providence Journal in the coming days.

At the time of the attack, just after 7 pm on January 15, 1972, two men were parked adjacent to her car. Charles Slack, an elderly gentleman, was visiting his sick wife with his nephew, Carl Salisbury.

Salisbury came to the aid of the woman, a part-time hospital dietician and student, pulling the metal chain off his dog and swinging in vain at the man with the knife. At the encouragement of his uncle, he ran into the hospital to alert the police.

As the men retreated, the woman was dragged at knifepoint to a nearby vacant apartment. The house itself was a straight shot from the parking lot, but the kidnapper took the woman three blocks further south of the hospital. They crossed Broad Street, past both a market and gas station, and cut up through yards and side streets to a second floor apartment at the end of Willard Avenue, according to police. It is a 10-minute walk. Police suggested that there were witnesses to the abduction, but none were brought to testify.

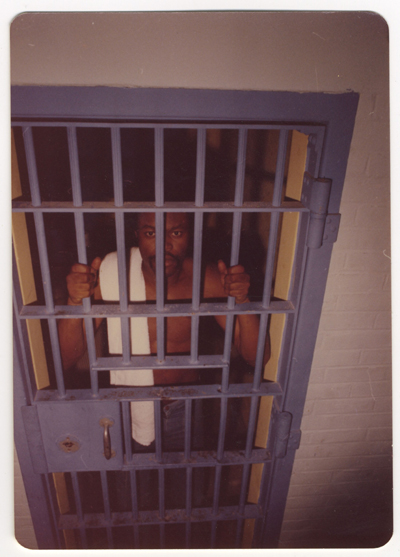

THE EARLY YEARS Spivey, pictured not long after he was convicted. |

The woman was kept in this apartment for over an hour, assaulted brutally and raped twice. She would testify that her captor told her that he hated all white people and was going to kill her.Salisbury's call to the police launched a search that involved over 40 policemen, with many going door-to-door. Shortly after 8:30 pm, police would tell the Providence Journal, the abductor was spotted dragging the victim across a vacant lot and he released her as a chase began. Several shots were fired, before police arrested their suspect at the corner of Chester and Taylor.

The suspect was Clarence Spivey, 19, of Marlborough Avenue. He lived a short distance from the house on Willard Avenue and was two months out of prison — on parole for juvenile offenses, with another pending charge against him. In November of 1972 he was found guilty of rape, assault, and kidnapping and sentenced to 55 years imprisonment.

"It is one of the most outstanding pieces of police work I've seen in the 26 years I've been on the job," Major John Eddy told the media following Spivey's arrest. Policing in Rhode Island needed a win at the time. Departments in Providence, Cranston, and Coventry had been hit by scandal, and the reputation of the state's prisons was at a low.

Few people questioned Eddy's assessment of the case until ten years ago, when Spivey's case caught the attention of the New England Innocence Project (NEIP).

An investigation by the Phoenix, following on research conducted by NEIP, has taken in hundreds of existing documents, old newspaper reports, barely seen copies of FBI forensic tests, and a partial copy of long missing trial transcripts from Spivey's brother.

It has, in the process, unearthed a series of lingering questions about the conviction of Spivey. He was found immediately following a brutal rape and assault but no physical evidence linked him to the victim; the FBI forensic expert at the trial was later fired for repeatedly perjuring himself; despite presenting alibis for the entire time of the kidnapping, Spivey was convicted by an all-white jury relying on eyewitnesses, all of whom saw Spivey in darkness. And, curiously, virtually all the original evidence and documentation of the case is nowhere to be found.

Today, at 59, Spivey is an inmate of the medium security wing of Rhode Island's Adult Correctional Institution. He is adamant that 40 years ago he was walking home after stopping by a youth center to inquire about a possible job when he was incorrectly arrested.

Somewhere in the fog of passing decades, the window for definitive answers has likely closed. But the succession of unanswered questions and scattered evidence that remain belie the certainty with which Spivey was sent to spend his adult life in prison.