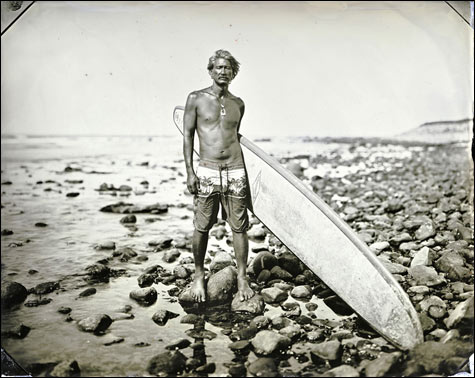

HAWAIIAN ED Sternbach’s best photos capture the feeling of people shaped by the elements. |

What's the difference between art photography and fashion photography? That's the question I kept wondering about at Joni Sternbach's "SurfLand" exhibition at Salem's Peabody Essex Museum. It features 19th-century-style tintype shots of surfers posed on New York and southern California beaches — sun-dappled bikini babes, sinewy dudes, athletic ladies and gentlemen squeezed into wetsuits, and grizzled old coots. They're all beautiful and sexy, even the gawky youths and the grizzled guys.The Brooklyn photographer's old-timey technique makes them seem straight out of the mists of the past. Only the fashions — those wetsuits — betray that these shots were made from 2006 to '08. It's wicked cool and gimmicky, all at once — and not much different from leafing through an American Eagle or Urban Outfitters catalogue.

What makes these photos feel that way? Secondly, is that okay? And, thirdly, why can't I get over my critical self and just give these photos some love? ESPN surfing blogger Jon Coen called them "authentic, rich" and said, "when I consider what went into each shot, I'm floored." And the Globe's Mark Feeney gave them a thumbs up, saying, "These images have an innate elegance."

Admittedly Hawaiian Ed is a striking shot. He's the old man of the sea perched on rocks at Montauk, New York, in 2008 with his long board balanced under his arm. He wears a bone necklace and palm-tree shorts as he squints into the sun, his hair blowing in the salt breeze. His body seems to have been bronzed and then sanded smooth by the bright sun, rocks, and waves — like driftwood or beach glass.

Sternbach's best photos capture that feeling of people shaped by the elements. The effect is amplified by the vivid materiality of her method. The tintype process, invented in the 1850s, prints images on specially prepared metal sheets, in this case aluminum. Preparation to developing must be completed before the chemicals dry, so everything must be done on the spot. Inside a dark tent, she pours collodion onto a plate, then dips it in photo-sensitive silver nitrate (collodion helps nitrate stick to metal) and loads the plate into a traditional view camera. The chemicals are less light-sensitive than contemporary stuff, so exposures take two to three seconds. Then she returns to the tent to develop the shots. No negative is created; each image is a unique print, which gives them an improvisational quality — accentuated by the varying drips, splotches, and halos, which themselves suggest the spray of the sea.