“Harvard and McLean have very high standards and I have fierce loyalty to them,” explains Halpern, obviously couching his words carefully. “If I am going to ask the institution to do something that is potentially stressful in the public eye, it better darn well be for the right reasons.”

Dr. James Fadiman, for one, thinks the cluster-headache work is a novel piece of research. “But this kind of work doesn’t say much about psychedelics,” says Fadiman, who is a psychologist with long ties to the psychedelic community (including experiments with Leary) and who is co-founder of the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology in Palo Alto, California, which trains clinicians to focus on states of higher consciousness and the spiritual dimensions of human experience. What Fadiman wants to know is not how well LSD works on headaches, but the mechanism that makes it work. “For example,” he asks, “do the headache sufferers experience an out-of-body awareness?” The medical community accepted acupuncture only when it was proven that it heightened endorphins. Without some existing model to measure it by, the medical community won’t accept LSD as medicine, no matter the patients’ claims that their headaches have stopped.

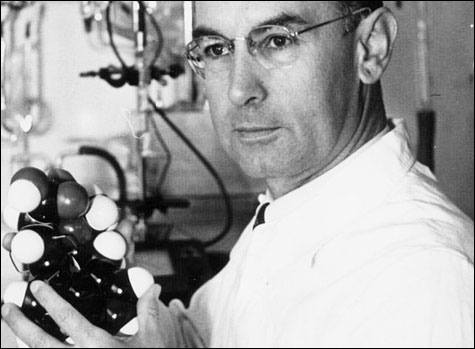

PIONEER TRIPPER: In 1943 Albert Hofmann synthesized LSD and experienced “an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors.” |

The three-headed beast

Imagine you are standing before the gate of Hades, which is guarded by the three-headed dog Cerberus. But instead of ripping you to shreds, he offers you some choice acid and a detailed map of the underworld. The world of psychedelic drug use is not unlike this friendly, electric-Kool-Aid-doling version of the ultimate hellhound. The first head is that of the drug-adoring hippies who grow their own mushrooms and continue to nurture conspiracy theories about the drugs while they search for a mystical experience from them. The second belongs to the scientists: people like Halpern; Roland Griffiths, who led a study in psilocybin and mysticism at Johns Hopkins; and Rick Strassman, whose 1990 then-radical research into DMT — the powerful drug found in the psychedelic drink ayahuasca favored by South American shamans — opened the door for legitimate psychedelic research, research done under very controlled and rigorous conditions. And the third head is a weird conglomeration of the other two, typical of such folks as Daniel Pinchbeck, who lauds the spiritual benefits of DMT and uses a kind of pseudo-science to, er, chart the date of the apocalypse, all the while having serious and sober proclamations to issue about the environment and technology. But many times — particularly when tripping on some fine blotter acid — these heads merge into a single face.

At the World Psychedelic Forum in Basel, Switzerland, this past March, those in attendance included Pinchbeck, the psychedelic artist Alex Grey, and a number of ethnobotanists, shamans, psychics, psychiatrists, and chemists — including Hofmann — to name a few. That all these individuals could unite under the umbrella of their interest in psychedelic drugs points to an underlying shared concern: is there a future for psychedelics outside of Phish concerts? And can this be achieved when, alongside those doing serious research, there are those who believe themselves to be reincarnations of Quetzalcoatl?