IT’S BLUE But is that really the problem? |

The set is black and white — dark modern chairs and table against a pale grid of a screen, like a vertical drop-ceiling. But what happens on this stage is a study in psychological grayscale, and the title of the show, Blue/Orange, suggests even more colorful oppositions in Joe Penhall's smart comedic drama about the vicissitudes of psychiatry, a patient, and his practitioners. It is on stage at Portland Stage Company's Studio Theater as the inaugural production of the brand-new Dramatic Repertory Company, under the direction of its artistic director, Keith Powell Beyland.

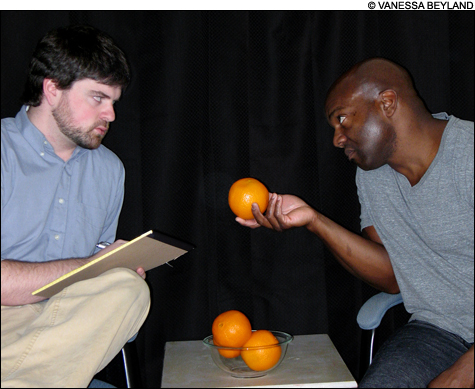

Christopher (Kevin O. Peterson), a young black man, is at the end of a month-long stay in a London psychiatric hospital, having been diagnosed with "borderline personality disorder" after a delusional episode. He claims to be the son of a Ugandan dictator, and to see oranges as blue. But now the "borderline" part of his diagnosis is a matter of fierce contention between his young doctor-in-training, Bruce (Evan Dalzell, recently in Mad Horse's Six Degrees of Separation) and Bruce's sardonic older supervising psychiatrist, Robert (Pope Brock): Bruce is convinced that Christopher needs to be held further, while Robert wants to let him go, insisting that the diagnosis has been culturally determined on account of Christopher's race. As the two doctors jockey for position, shamelessly using the patient as a wedge, they reveal a disturbing spectrum of subjectivity, power dynamics, and ulterior motives at play in the science they practice.

As the elder therapist, Brock immediately asserts a monstrous and narcissistic superiority — one of the first things we hear out of his mouth, after a compliment of Bruce's wife's cooking, is the advice that Bruce should "tie her to the nearest bed and inseminate her immediately." Brock does marvelous things with his face and tone to convey Robert's effete arrogance: Eyes widen, lips stretch in condescending grimaces, and he perfects that certain patronizing vocal upswing of "Ok?" and "Hm?"

Bruce, on the other hand, is insecure both in his career and his role as therapist. Some of his lines to Christopher reveal fairly mind-blowing maladroitness (one gaffe of reverse psychology finds him insisting it would be easier for Christopher to rejoin all the uninstitutionalized people out there enjoying their illegal drugs). Bruce is yet unformed as a psychiatrist, but he also feels somewhat underdeveloped as a character. I'd like to see a little more fire behind Bruce's naivete, and for Dalzell to let him agonize a little more over his frequent ineptitude. Dalzell gives him much more convincing animus as he gets angrier, more desperate, and more bitter.

As the pawn in the doctors' dueling, Peterson does a difficult job quite well — he convincingly conveys Christopher's twitchy anxiety, his fearful delusion cut with equally fearful self-knowledge, and his helpless suspicion of both doctors. In the few moments written for Christopher to surge, his anger and fear are a primal force over the other men's self-serving platitudes.

We hear quite a lot of their platitudes and witty one-upmanship, enough so and with sufficient repeating themes that a tighter pacing would serve the show well. As it is, timing at times drags in the doctors' verbosity, particularly during Brock's monologues, when he sometimes seems to be searching for lines.