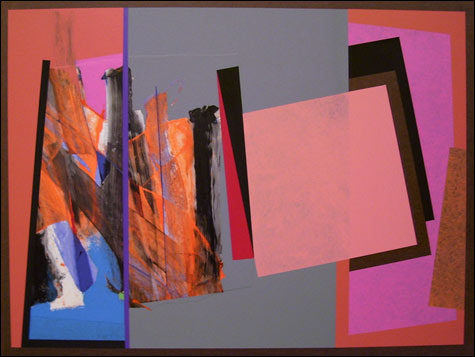

ANALYTIC EXPRESSION “Painting #324,” 2011, acrylic on Masonite, by Bill Manning. |

Bill Manning has been a central figure in contemporary art hereabouts for something close to five decades. He started showing his work in 1960 and over the years has had dozens of exhibitions here in Maine, in New York, and in many other places. He is a dedicated abstract painter with a deep understanding of modernist thought and its function in artistic, and that is to say human, perception.

His influence can't be overstated. In the late '60s he started what was called the Concept School, after being fired from the Portland School (now the Maine College) of Art following a fundamental artistic disagreement with the management. Concept only lasted about four years and yet produced way more than its share of artists with accomplished careers, among them Katherine Bradford, Don Voisine, and Noriko Sakanishi.

The 25 recent paintings and drawings in the current show at Icon Contemporary Art in Brunswick demonstrate once again the nature of his thinking about how we apprehend the visual world and apply our human understanding to it. At a recent gathering in those rooms a veteran art-watcher and writer asked Manning how he would teach someone to draw. Manning replied, without a moment's hesitation, "If you can write in longhand, you draw." This is correct, and makes a couple of essential points: Drawing has been the same since long before writing was invented, and it is always an abstraction — technical details are just that, details. It's important also to note that the drawn rendering of, say, a rock's shadow is not a really a shadow — it is marks that convey an abstraction of a particular experience (looking at a rock with a shadow) from one person (the artist) to another (the viewer). We can follow this analytic, expressive thinking quite directly in Manning's work.

For example, "Painting #324," 2011, acrylic on Masonite, takes its undertone from the mottled brown of the support, carried unchanged around the border of the four-foot panel. Hard-edged shapes of fairly thin color on the right produce both a rhythm and a slightly modulated illusion of space. A large gray section occupies the center of both the panel and the viewer's attention, and supports a discrete area of activity. Some of this section is executed on a collaged area where paper has been glued on the Masonite, effectively blocking the brown undertone from affecting the final color. There are denser colors here, as well as some loose, improvisational paint handling. Stripes and hard-edged shapes of more saturated color provide counterpoint.

There's an old truism in jazz that there are no rules, but there are reasons; this guide may be applied to visual art in general and Manning's paintings in particular. Color values and hues create their own dynamic with respect to each other, as do shapes and tones. Things advance and recede in illusionistic space, producing their own syncopation and order. Nothing here is left to chance, even the areas of improvisation. The elements are not representational, but they are relational, each to another.