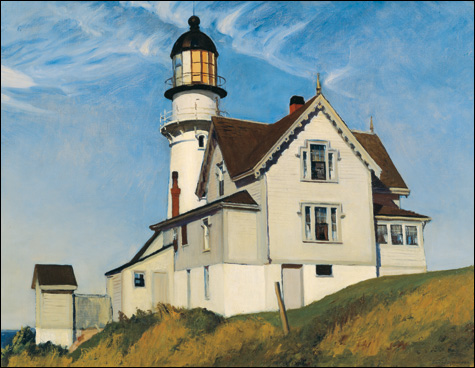

‘CAPTAIN UPTON’S HOUSE’ Oil on canvas, 28 by 36 inches, by Edward Hopper, 1927. |

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) occupies a singular place in the history of American art in the 20th century. He lived most of his life in Greenwich Village in Manhattan, with occasional forays in summers to coastal New England. A few of these trips, especially in his formative years, were to Monhegan and other parts of the coast of Maine. The work done in the Pine Tree State is the subject of "Edward Hopper's Maine," the current show at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. This show provides significant rewards to the visitor, as any Hopper show is bound to, but it also raises some questions.

>> SLIDESHOW: "Edward Hopper's Maine" at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art <<

My own history with Hopper goes back 40 years or so when I first encountered his work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. I was immediately attracted to the paintings' narrative depth and psychological insight, an interest that has, if anything, grown over the years. His work is subtle but accessible, and possessed of a poetic radiance that sets it apart from any of his contemporaries and, as far as I know, from any other narrative painter of his time. His achievement sustains itself over the long haul, and his influence shows up in the most unlikely places — Mark Rothko, Willem deKooning, and Jim Dine all point to Hopper as inspiration.

In the past he was compared to his contemporaries Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, who also painted indigenous American scenes, but that comparison hasn't held up. Wood and Benton were, in Hopper's own words, caricaturists, and putting them in the same sentence is like pairing John O'Hara with Henry James — Hopper's accomplishment is of a different, much higher order of magnitude. He also far outstripped his fellow Robert Henri students George Bellows and Rockwell Kent. Bellows captured some memorable scenes but didn't live long enough to fulfill his promise, and Kent went on to his adventures and his radical politics. Hopper spent his long career building a truly profound body of work.

Hopper traveled to Maine in 1914 as a Henri student, first to the artist's colony at Ogunquit and later to the informal Henri colony on Monhegan. The works he did then, in the teens and in a later trip in the mid -1920s, are the basis for the Bowdoin show.

When Josephine Hopper, Edward's widow, died less than a year after he did, she left their collection of some 3000 paintings to the Whitney, which has loaned quite a number of mostly very early paintings to Bowdoin for the exhibition. "Blackhead, Monhegan," an oil-on-board about eight by twelve inches, was executed between 1916 and 1919, and is fairly typical of this group of early paintings. It's not exactly a study, but it doesn't seem to be a formal presentation painting either. It was quickly done and shows Hopper's considerable armory of painterly skills. He seems to have been relaxing and finding his way toward something else. These paintings are enjoyable but are clearly developmental; without the imprimatur of the Whitney bequest they might have been difficult to identify as Hopper's.