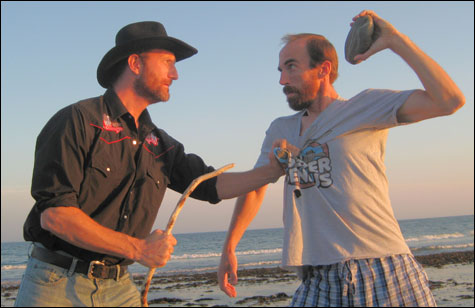

WHOSE LAWS? Their laws, broken in Best Enemies. |

Cody (G. Matthew Gaskell) has been a serial violator: "'Rack of beer,' 'buxomy,' talking to yourself," accuses Rex (Don Goettler). "That's three laws in three minutes." His verbal transgressions fly in the face of laws enacted in a from-scratch, Survivor-style civilization of two, and they're punishable with a day of hunger apiece. Such are the rules and the stakes in Michael Kimball's Best Enemies, a desert-island "comedy about cowboys," which Leslie Pasternack directs at the West End Studio Theatre, in Portsmouth.

Cody and Rex are the sole inhabitants of their personal land, a tiny, treeless, and very hot island, deposited there after their rodeo cruise ship blew up. Rescue has not proved forthcoming, and as the landscape doesn't provide much in the way of diversion, Cody and Rex have spent their time making games, and later war, around the bare essentials — Hat, Stick, Rock — and crafting laws born of their situation: No threatening with Stick. No yelling "Boat." Rex has gone on to create a virtual landscape — a mountain, shade trees — whose "laws of geography" must be respected, and his laws become increasingly strange and stringent. The tension mounts as the elements and the cowboys' judicial distortions take an increasingly mortal toll.

I first reviewed this show in 2006, when it premiered across town at the Players' Ring. This most recent production, with its particularly nice desert-island set (a speckled sheet that ripples amazingly like sand, bordered with blue) seems to draw a more stylized contrast between the two cowboys: With Goettler's low, menacing, fine-gravelled voice and squinty eyes, he's the archetype of the hard-calloused wrangler. His severity and seething rage contrast sharply with the loosey-goosey babble and general comedy of Cody (who is, in fact, a rodeo cowboy), whom Gaskell portrays with just about exactly the chirpily persistent intonation of the guy you hope you don't find in the next airplane seat. Gaskell also does a fine, subtle, and empathetic job of gradually revealing Cody's substantial understanding of human nature, even that of the completely cluster-fucked, stranger-to-himself Rex.

What I found most compelling about this show in my original viewing was how cleverly and elegantly it used its absurdist premise and the emotional contrasts of its characters to meditate on the sources and implications of human law. Through the rules of the repressed, furious Rex, we explore how natural law, said to rely on reason to define moral codes and so to be based on universal human nature and needs, can become perverted, leading to a set of seemingly arbitrary and absurdly stringent commandments.. The more we learn about the angry, insecure, and deeply damaged foundation of Rex's psyche, the more his laws — most pointedly, "No talking about women" — make a twisted, tragic sense. The laws of this island are based neither on pure reason nor on wacko arbitrariness, but on anger, insecurity, and suffering: emotions we've seen as popular motivators for some of the greatest human atrocities, and emotions which are arguably at hand in our current cultural moment. Which is all to say that Best Enemies makes an extraordinarily trenchant point about human governance.