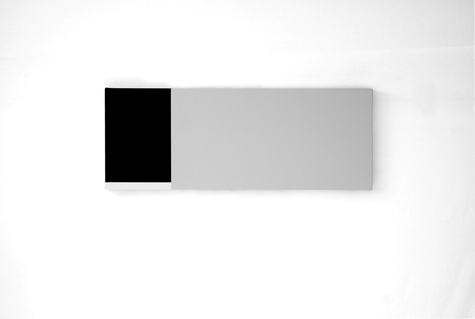

'NO ONE'S EVER SEEN THEM' Acrylic on canvas, 12 by 32 inches, by Martha Groome, 2012. |

Encountering Martha Groome's paintings forces one to slow down, observe coloristic and spatial relationships, and ultimately tune in to the works' quietude. Nineteen of the artist's newest paintings are on view at ICON Contemporary Art in Brunswick; potential visitors must hurry as the show closes on June 23. Rushing over there is well worth it, though — Groome's paintings are strong and extremely rewarding to experience.

While varying in size, all works are in Groome's signature style of squares and rectangles of unmodulated color, in this case hues of gray, cream, black, and blue. Beyond variations in the paint's reflectivity, surfaces are featureless, which appears integral to the artistic intention. Groome's work is all about ratios, relationships, and subtle formal and coloristic differences. Rectangles oriented horizontally or vertically assume a variety of functions, delineating, framing, or conveying weight. Several pieces are comprised of a large square or rectangle that is bordered on one side by smaller ones, upsetting the stasis of the larger expanse and energizing the entirety of the canvas. In "Blue Parts," for instance, a horizontal light blue rectangle is adjoined on the right by a black square stacked atop a vertical rectangle of darker blue. These arrangements read as absolutely flat without a hint at spatial recession, although some configurations play optical tricks on us with after-images and variations in color that are not really there. There are though actual subtle variations in the two whites and blacks of "Two and Two" which may easily be missed. These create stillness out of near nothingness.

Groome exerts an exquisite control over compositional forces. The spatial ratios between individual fields of color are calculated to maintain a balanced weight amidst their energetic discontinuities. Her brand of extreme pictorial reduction goes all the way back to Kasimir Malevich. Aiming for a geometric abstraction that avoids subject matter and representation of the external world, even Malevich's non-objectivity was not without associative content — spatial, sensory, emotional, and spiritual. Aside from their formal strength and extreme simplicity, colors and configurations in Groome's paintings too suggest a world of experience beyond the confines of canvas and paint. "Box in a Box" suggests an opening or even a doorway, and other paintings bring nondescript urban walls to mind. Because of where we are, light blue expanses may evoke water views, which I initially found almost distracting, until I allowed this second reality to coexist with the purely formal one. Another avenue for associations is supplied by the titles, or "names," as the artist calls them. Part of them seem like narrative bits or found objects; others read like descriptions of the compositions or commentaries on the work with a Duchampian sense of alienation and humor. All this just seems to prove that no abstract work is without something the human mind could latch onto for an association. It only requires a little time and focused openness. While some abstract artists resent this tendency and do their best to discourage it, Groome is clearly not one of them.