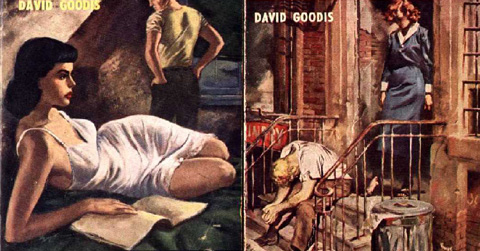

HAUNTING Capturing a dank atmosphere perfect for film noir, Goodis's novels have been adapted by the likes of Jean-Jacques Beineix and François Truffaut. |

That a print can be left in dried blood suggests how sloppy Goodis can be. But we don't question it because we're immediately caught up in the morbid grief of Goodis's hero:

Then there was a sound of a man's footsteps coming slowly along Vernon Street. And presently the man entered the alley and stood motionless in the moonlight. He was looking down at the dried bloodstains.

The man's name was William Kerrigan and he was the brother of the girl who had died here in the alley. He never liked to visit this place and it was more on the order of a habit he wished he could break. Lately he'd been coming here night after night. He wondered what made him do it. At times he had the feeling it was vaguely connected with guilt, as though in some indirect way he'd failed to prevent her death. But in more rational moments he knew that his sister had died simply because she wanted to die. The bloodstains were caused by a rusty blade she'd used on her own throat.

At the beginning of Nightfall, Goodis describes the air of a New York summer night as "syrupy heat [that] refused to budge." He could be talking about the atmosphere of these books. None reaches 200 pages, but none is a fast read. You wade through the resigned torment of Goodis's men, conscious that at any moment the thick, obsessive mixture of fear and guilt might close over your head.

In Goodis, psychic architecture determines not only the physical world but narrative as well. If you just go by the plots, Goodis's books make no sense. They proceed less by consequence than by the vagaries of a guilty mind, though in only one of these five novels has the protagonist committed a crime. Goodis would have been lost if he'd had to produce the concrete detail which moves a procedural forward. The cops and crooks and thugs and jilted lovers who come after his wounded, haunted men seem to have been conjured up in the protagonists' own turbulent minds. At times, it's as if we are in the world of a science-fiction author who has realized a future where people are tracked by their own brain waves instead of fingerprints.

This is how we're introduced to Dave Vanning, the artist of Nightfall, contemplating New York in a heat wave, and the possibility of ever getting out of the fright that shadows him:

Heat came into the room and settled itself on Vanning. He lit a cigarette. He told himself it was time for another drink. Walking to the window, he told himself to get away from the idea of liquor. The heat was stronger than liquor.

He stood there at the window, looking out upon Greenwich Village, seeing the lights, hearing noises in the streets. He had a desire to be part of the noise. He wanted to get some of these lights, wanted to get in on that activity out there, where it was. He wanted to talk to somebody. He wanted to go out.