MAINER'S WORKMANLIKE APPROACH Samuel Colman's "Cliffs at Étretat," c1873, eschews metaphysics in favor of a skilled watercolor. |

Walking across the first gallery at the Portland Museum of Art's fine exhibition, "The Draw of the Normandy Coast: 1860-1960," you encounter three paintings of the same subject that outline three of the different ways of thinking that were part of artistic life in the period. They all depict the famous Manneport at Étretat, an arch-like geological formation that stands in the sea like a natural flying buttress.

Those three paintings (out of several more of the same subject) are by Claude Monet, George Inness, and Samuel Colman. Here are, as if for comparison, distinct artistic world views. Inness, for example, was looking for spiritual expression, not unlike that of his predecessors of the Hudson River School but more explicitly theological. Influenced by Swedenborg, Innes sought the divine in his own experience and wished to express it in his paintings.

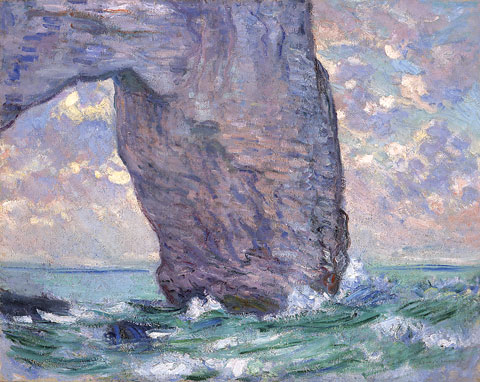

Monet, the very model of an Impressionist, looked instead for the reality of the sensations he could detect. The colors are laid down in local strokes that build up to a sense of the light, as if he could distinguish the physics of what was occurring. He was more the Kant objectivist than the mystic Inness, seeking the true nature of what was happening to him on the spot.

Samuel Colman is the Yankee from Maine in this group, out to get a straightforward representation for his American patrons. There's no fancy metaphysics here, just a skillful watercolor executed at a special spot where many others had worked. Colman was also an interior designer who worked with Louis Comfort Tiffany on Mark Twain's house in Hartford. It's an enjoyable, workmanlike effort, very Maine.

It's tempting to draw parallels between the Normandy and Maine coasts — both drew tourists and artists, and a great many paintings have been made along both shores. The seashore attracts vacationers, and the lives of the locals were and remain a popular subject for images. Artists on both coasts have served as anthropological documentarists, much as photographers do now.

But the comparison doesn't hold water. In the latter 19th and early 20th centuries, the Normandy coast was the summer gathering place for aristocrats and high bourgeois of Belle Époque France. The chateaux were big, the hotels grand, and the dress elegant. Proust spent much of his time and his novel there, and his narrator Marcel first sees his lover/nemesis Albertine on the beach in Cabourg (Proust's Balbec). Some of Proust's wonderful descriptions of paintings bring Monet instantly to mind; others recall Whistler, also in this show. By contrast, with the exception of Bar Harbor there was little elegance associated with Maine's summer culture. In Maine people lived pretty rough. In those days everybody with any aspirations to artistic seriousness went to France.

A SENSE OF LIGHT "La Manneporte Vue en Aval (The Manneport Seen from Below)," by Claude Monet, c1884. |

And, in the summertime, often to Normandy. Moving through the show reveals echoes of the diverse threads that ran through much of Western painting in the show's period. The archetypical Realist (in the art-historical sense) painter Gustave Courbet, much given to an uncompromising combative relationship with his viewer, painted the same cliffs as Monet and Inness and came away with "Stormy Weather at Étretat" in 1869. No smiles and sunny grace here, just waves, seabirds, and rocks. In the Courbet portrait, "M. Nodler, the Elder at Trouville" (1865), the sitter, with his back to the beach, has a wary but dignified look. Perhaps he had concerns about a rendering by the revolutionary firebrand Courbet.