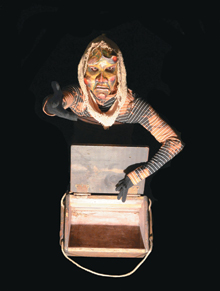

MADNESS IN THE DARK A demon from The Medicine Show. |

We gather in the dark and the stray beams of each other's flashlights, on the edge of fields and woods just shy of Merrymeeting Bay. Three or four figures have apparently come this way before, and they are spontaneously tapped to serve as "ushers" for the rest of us: They wave their beacons in the air, we draw close like moths, and all proceed for some minutes along a rough road of wet grass and uncertain footing. Finally, we approach a light in an open field, where a man in a top hat and vest is singing and drinking a brown liquid from a glass flask. This is our overture to The Medicine Show, the new and elemental production from the Ziggurat Theatre Ensemble, written by Stephen Legawiec and directed by him and Dana Wieluns Legawiec , and performed, just in time for Halloween, under the moon in Bowdoinham.After this summer producing a gorgeously appointed, sophisticatedly stylized detective-fairy tale, complete with a Magritte motif and a chorus of urbane French chanteuses, Ziggurat now mounts something completely different: A primal, bare-bones, low-lit, nearly wordless spirit encounter of masks, pantomiming, and movement, outdoors and in the dark, against a background of tall trees and one plain backdrop lettered with the words "The Birds."

That's the title of the show we're not going to see, says the fellow with the flask (Stephen Legawiec). It turns out he's the "driver," or manager, of a medicine show — one of the traveling acts of 19th and early 20th century America that performed song and dance for the residents of each new town, hoping to warm them into buying the snake oil and miracle elixirs that were often useless and frequently worse. But there'll be no show or tonic sales tonight, the Driver tells us, because his troupe is dying off. Three have died already, and the last six are en route, cared for only by a haunted foreign girl (Michela Micalizio). What we'll get instead, tonight, is a different kind of "medicine," loosely evoking Abenaki legend and the tradition of healing through dealings with the spirits, as a boy with a lantern (Dylan Chestnutt) approaches the camp, then dreams his way into the demons' mischief.

These demons (Astrea Campbell-Cobb, Laura Christman, Kyle Dennis, Lilly Victoria Gardiner, Hillary Perry, and Ben Proctor), garbed in spooky, grinning masks (by Wieluns Legawiec) tease and afflict the Boy with primitive movement, pantomime, and physical comedy: A slinky succubus sighs and shakes over something vaporous she adores in a wooden box. Twin girls repel and attract him in a crude dance. A red-faced man and a pink-cheeked, grimacing woman manipulate him like a puppet into slapping himself in the face. The demons make low, scarily indefinable sounds. The demons simply stare.

They are startling. The setting and sparseness of this production make these and other simple visuals and sounds especially striking: After our eyes accustom to two low lights and a world of black beyond, we see the Boy's bright lantern approaching from a distance. After our ears adapt to long silences, we hear the Girl's rough, forceful syllables of a Slavic-sounding language. The show might benefit, in fact, from further stripping down in the early part of the show; as it is, the Driver's introductory remarks feel too expository for what follows — I'd love to see his preliminaries starker, drunker, and more guttural.