The author of The Lost Weekend gets a lift from a new biography and a couple of reprints

By CHARLES TAYLOR | March 18, 2013

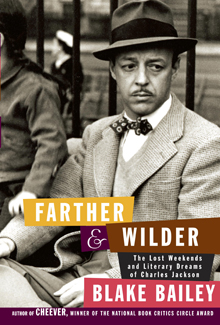

F. Scott Fitzgerald claimed there were no second acts in American life. Do posthumous ones count? If not, Fitzgerald himself would have been forgotten, his work being almost completely out of print by the time of his death in 1940. Charles Jackson has been forgotten, if contemporary readers ever knew him in the first place. Even his most famous work, the 1944 novel The Lost Weekend, is better known today for its film adaptation directed by Billy Wilder in 1945. I don't know that anything would have changed if Blake Bailey's new Jackson biography, Farther & Wilder: The Lost Weekends and Literary Dreams of Charles Jackson, hadn't prompted Vintage Books to release a new edition of The Lost Weekend and a slightly reordered version of Jackson's 1950 collection The Sunnier Side and Other Stories. If I'm honest, then I have to admit that next to a rediscovery like this, the contemporary world of fiction doesn't seem much worth caring about.Bailey, in his acknowledgments, explains that Jackson's life presented an opportunity to examine why in some writers, talent isn't enough, why some fade into oblivion, while others with problems similar to Jackson's (such as Bailey's previous subjects, John Cheever and Richard Yates) maintain their visibility and reputations. The Lost Weekend made Jackson famous; yet by the mid-1950s, he was struggling to finish manuscripts, eking out a living writing scripts for television dramas and working at J. Walter Thompson advertising agency, where he vetted others writers' scripts for their appeal to suburban viewers. All the while, Jackson was relapsing into alcoholism and dealing with his partially closeted homosexuality (known to his wife and, eventually, his two daughters). Jackson had a final bestseller in 1967, A Second-Hand Life, and the following year took a fatal overdose of Seconal in his apartment at the Chelsea Hotel.

|

Bailey, scrupulous and sympathetic to his subject, spends some time on why Jackson himself believed he became an alcoholic and gay. The reasons — his father abandoning the family when he was young and his relationship with his mother — reflect a simplistic Freudian interpretation that, luckily, is not found in Jackson's fiction. The reality of The Lost Weekend is so strong that any causes offered for the torments of its protagonist can only seem a reduction.Almost 70 years after its initial publication, The Lost Weekend remains unmatched as a merciless and compassionate explication of the drunk's psyche. (As revered as it is, Malcolm Lowry's Under the Volcano is fatally weighed down by its devotion to a mythology that is both subconscious and schematic, and that makes it nearly impossible to read.) Jackson's book takes place over a long weekend during which protagonist Don Birnam had planned to go with his devoted brother to the family's country retreat. But Don ducks out, and the days that follow are measured in hours, sometimes minutes. How long till the bars or the liquor stores open? What streets can Don walk down and not encounter merchants he's cadged money from? Jackson's descriptions of Manhattan blocks in the 1950s, of pawnshop windows on Second Avenue, have the exactitude you find in Edith Wharton or John O'Hara. He's writing in a strain of American realism that, as Don's seams come apart, approaches the hardboiled and finally the hallucinatory. The mundane is raised to the level of the totemic as Don counts up how much money he has left to see him through the weekend or measures the booze left in his pint. It's a book in which small efforts — cleaning up, leaving the house — are assayed as if scaling Everest. It may give some idea of the book's fearsome power that whenever I put it down, I hesitated to pick it back up. But when I did, I felt in the grip of something I couldn't get out of — for pages and pages at a time.

Related

Related:

Generation gap, John McCain's economic philosophy, Twitheads, More

- Generation gap

It’s an uneven show with a dour vision that leaves a mediciny taste in your mouth — and, I think, offers signs of a generation gap among curators.

- John McCain's economic philosophy

Big Fat Whale

- Twitheads

Is Twitter bad for journalism?

- Opening pitch

The most moving moment of this year’s Boston Symphony Orchestra opening gala came before the concert started — the standing ovation for James Levine, who looked rested and recuperated after his kidney surgery this summer, an operation that forced him to cancel most of his Tanglewood season.

- Peter Bjorn and John | Seaside Rock

It’s really pointless. And somewhat nice.

- Mobile-home game

The intersection of Brookline Avenue and Lansdowne Street, in the hours before, during, and after a Red Sox game, is not unlike a trading floor on pre-crash Wall Street: it’s chaotic, teeming with people, and everyone’s trying to make a buck.

- Is John McCain crazy?

There is something not quite right about John McCain.

- Sweet release

I don’t want to waste your time waxing philosophical about the problematic logic behind qualifying music “good” or “bad,” much less pontificating on whether “sophisticated punk” is an oxymoron.

- Saving Marriage

Roth and Henning, dedicated partisans, were everywhere with their cameras in those historic years 2003–2006.

- Living la vida Republican

Trying to find college Republicans in Boston is like looking for a flattering pair of jeans: they’re elusive — either too stiff or completely out of style.

- Filth and Wisdom

As the lead character narrates his “filthy” story, and those of his London flatmates/neighbors, we hit upon boredom long before wisdom can arrive.

- Less

Topics

Topics:

Books

, Malcolm Lowry