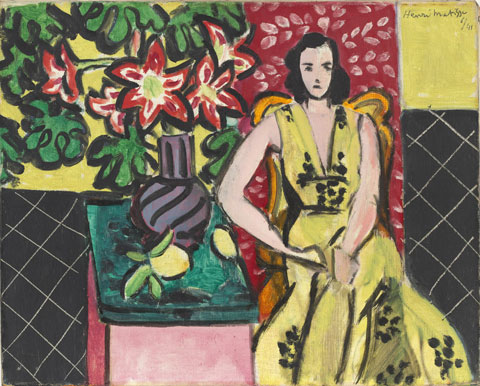

'SEATED WOMAN WITH A VASE OF NARCISSUS' Oil on canvas, by Henri Matisse, 1941. |

It's a peculiarly American irony that the same man who basically invented the advertising model for the business of broadcasting radio and later television would have amassed a significant collection of modernist art. The financial ecology generated from Gilligan's Island and Winston cigarette commercials allowed William S. Paley to own works by major figures of Western art, artists who developed and embodied a set of ideas that changed the way we see things. Low mass culture bought high art.

Paley collected works that ranged from Cézannes made in the 1880s to the lyrical abstraction of Kenneth Noland in the late 1960s, acquiring in the process works by such canonical modernists as Picasso, Matisse, Derain, Miró, and others. The current show at the Portland Museum of Art includes a selection of 62 works by 24 artists from Paley's collection, most of whom are generally accepted as central to the modernist idea. When Paley died in 1990 his collection went to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the source of this traveling exhibition. The Modern has established, over the years, the defining parameters of the modernist canon.

One can sense the footsteps of Alfred Barr in this show, and of the formative years of the Museum of Modern Art in the 1930s and '40s. Barr was the Modern's first director starting in 1929, and stayed there in one capacity or another until 1968. He was largely responsible for the outlines of the modernist canon as it has been received in art history in the late 20th century and as it remains, even as the limitations of Barr's vision have become clearer. Paley was active on the board of the museum, the shape of his collection reflects guidance from Barr and others.

There is no arguing the impressive quality of the works in the this show, nor of the artists' influence on the whole of Western art. Any group that features works by Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse is grounded in the best that modernist ideas brought into being. There are five Cézannes, six Matisses, and eight Picassos.

Of the two major Picassos here, one is the accessible and popular "Boy Leading a Horse," 1905-06. The young Picasso was already gaining fame for his "blue period," but this is a transitional work, maintaining the pathos and atmospherics that had marked his precocious career up to that point. This painting, complex but unsurprising, was only a couple of years away from his groundbreaking "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon," painted perhaps in competitive response to Matisse's "Le Luxe II," itself grounded upon Cézanne's "Large Bathers" (none of which are in this show). The world was about to change.

You can see where these changes were headed in Picasso's "The Architect's Table," 1912, a high-water mark of analytical cubism. The picture plane was fractured, the artists had finally become the central actors in their own drama, and what had been learned was irreversible. By the time of "The Guitar," 1919 and "Still Life With Guitar," 1920, Picasso had settled into a method whose echoes can be seen every day, practically anywhere.