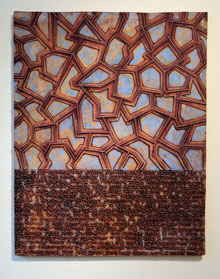

EXPRESSIVE COMMUNICATION 'Gate (Golden

Hour),' plaster, carpet, casein paint, and encaustic,

26 by 20.5 inches, by George Mason, 2012. |

George Mason has been a familiar presence in art in Maine for decades. His work is found in public places, schools, and private collections, but he hasn't often shown significant groupings of work in Portland. His current show of more than 20 items at the Maine Jewish Museum provides a broad look into his current thinking.

Mason trained as a ceramicist, and much of his work that can be found in public collections installed over the years is grounded in patterned assemblages. A large piece may have a distinctive overall design built up from tiles he has made for the purpose, a single piece made from custom parts. His work done in the past few years, though, has only a passing acquaintance with ceramics. In this current show he carries on with a recent project that involves large wall hangings.

Knowing an artist's process is irrelevant to knowing what the work is about, but in this case process and description are closely related. These pieces, some as large as a four feet square or more, are made from panels of, basically, tinted hydrocal plaster cast with fabric, and hang an a inch or so from the wall. The are built up of several adjacent and overlapping panels with colors that blend or interact with their neighbors. Mason works the surfaces with various tools and casts different shapes in low relief, carves them, and adds color, sometimes with paint or pigment or encaustic.

You read any of these pieces as you would a tapestry — a pictorial arena of intention and prior action that seems to gently drift, albeit without unicorn or damsel. They are attached to their hanging cleats with visible screws — the hardware and uneven edges restate their physicality and recount their production. These are, in a sense, very thin sculptures with what first appears to be informative actions on their surfaces.

The Maine Jewish Museum has undergone a restoration in recent years, and now is an elegant and inviting space. The exhibition space is a wide hallway and progresses up the stairs, and Mason's work hangs here comfortably. There is plenty of room to look at them as a successive group, and one can pass easily from one to another, seeking out the details in each.

The marks and glyphs that Mason applies to the fields of activity he has assembled are the key to his intentions. The pieces have a sensitive muscularity, an adamant physical presence that is palpable but not overwhelming. These things are unquestionably large and physical, but not demanding. You bring your own attention to them to see what's there because they quietly exist, not because they shout.

It's easy to be tempted to decode the marks and glyphs that populate the surfaces of these works, and to expect a message, real data. And indeed in works like "Refuge" there are letters inscribed in dozens of narrow vertical rows. One at first takes these for Assyrian Cuneiform, since the marks appear to have been impressed by a stylus, then cast as relief. There is a resonant echo here, since we are in the Jewish museum and there is a traditional calligraphic script of Aramaic still sometimes called Assyrian. Ancient lore of the early Israelites is tied closely to the history of Assyria, especially in the period between about 1200-700 BCE.