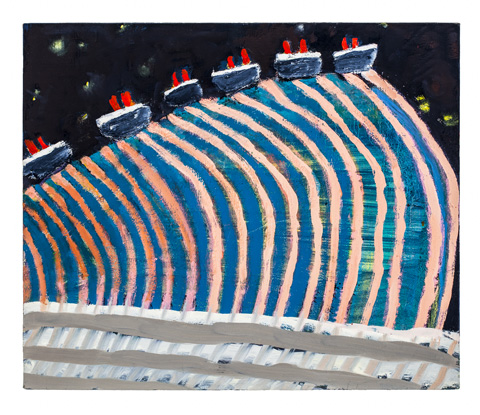

‘MILE HIGH LINERS’ Oil on canvas, 17 by 20 inches, by Katherine Bradford, 2012. |

With only eight paintings, “Katherine Bradford: August” at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art leaves us wanting more. Still, Bradford’s familiar ocean liners, swimmers, super(wo)men, and sunbathers give this little show a powerful punch.

Bradford is an influential and supportive member of the art communities in New York and Brunswick. A founding member of the Union of Maine Visual Artists, her many honors include fellowships and grants from the Guggenheim and Pollock-Krasner foundations, and having work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum, among others.

Style and subject matter of Bradford’s paintings reflect her dual residence. Intuitive and generous paint application aligns the work stylistically with the urbanity and abstraction associated with New York. Figurative elements on the heavily worked canvasses seem born out of paint.

Each work’s history remains partially visible, like strata of intuition and decision-making. The resulting luscious and dynamic surfaces richly reward being seen up close as well as at a distance.

For subject matter, Maine, its oceans and summer activities, in a generalized sense serve as inspiration. Bathers are recurrent themes in Bradford’s paintings, and maritime vessels of various shapes and functions have been a subject for a while too. Recently, ocean liners, rendered emblematically more than realistically, have become a focus of paintings and also crudely executed sculptures, even a hilarious video about the Titanic. Six of the paintings in “August” are of ocean liners.

The word “luminous” has often been used to describe Bradford’s work, and it certainly captures well the jewel-like quality of “Ship in Blue Harbor.” Much of the large canvas is taken up by the asymmetrical bulk of the ship looming darkly in the surrounding blue brightness. The water’s surface is dotted with rows of swimmers’ bathing caps, or incandescent highlights, or reflections of the ship’s lights, or simply star dust, giving the vessel a magical aura and transporting it into the realm of fantasy and longing. In Bradford’s world, none of this has to make sense.

Her images don’t present narratives in a conventional sense, but rather dream-like scenarios of possibilities. Rules of pictorial tradition, balanced compositions, believable recession into space, and the like, are abandoned. Instead, the ocean liners become symbols of mobility, aspirations, and hope, but also of possible doom. Note the jagged coastline in “Island Ferry” (one of very few images including land), jutting out like ferocious teeth waiting to maul the little ferry boat. Humor is an essential ingredient in Bradford’s work, and so is, against all appearances, tradition. Not only do these images project an intimate familiarity with painters of similar subjects, reductive tendencies, and atmospheric intimations who went before, including Albert Pinkham Ryder and Marsden Hartley, but they also continue a 19th-century notion of the sea as a metaphor for spiritual transcendence.

Bradford’s figures are heroic and awkward at the same time; so is the act of painting itself—trusting imagination on the one hand, and painting sloppily, but daringly, on the other. In “Sunbathers,” the rough shapes of two bodies seem like excuses for subject matter among daubs and crosses of paint almost liberated from signification. “Mile High Liners” beats all of the images in the show in sheer zaniness and unbelievability, as a fleet of ocean liners live it up atop a row of blue and pink lines. There is a refreshing nonchalance about these paintings, an unapologetic lack of concern with rationality and restraint that feels invigorating.