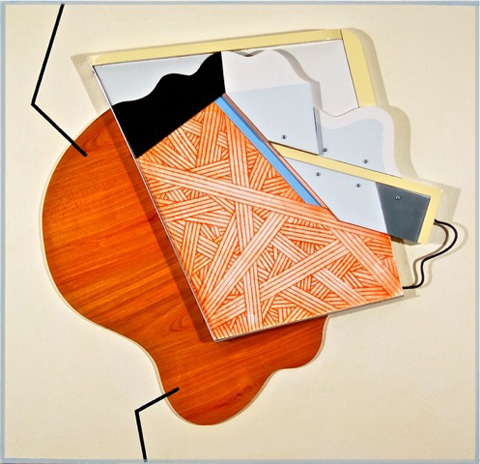

'Okie-Dokie' by Frederick Lynch |

'Painting 454' by William Manning |

What we have in the current show at Icon Contemporary Art is 20 or so works by two artists who have been around for the better part of a lifetime (and for anyone under, say, 40, for all of it), shown on two floors, Manning on one and Lynch on another. Both Frederick Lynch and William Manning are in their late 70s, both have taught others, and, more important, both have had a consistent arc over their long working careers. You can spot and identify works by either artist from a distance.

Other than that, which is a lot, and the fact most of these pieces have been done recently, Manning and Lynch don’t have a lot in common. The work is non-observational, to pretty much the degree that any artwork can be, and abstract, bearing in mind that all artwork is an abstraction. They set their terms and do what they do within the terms’ boundaries.

I found myself wishing several times, both at my visit and afterwards, that the gallery would have seen fit to mix their work together — part of the interest of seeing Lynch and Manning under the same roof is ascertaining any similarities in their underlying aesthetic principles and meditating on the differences. But the stairs between the upper and lower provide a little exercise, especially while toting a conceptual load up and down.

Bill Manning’s paintings are numbered, as befits a series that takes a basic material and theme and provides it with variations. It’s a set, and a large one: The works in this show are all numbered in the mid-400s, indicating there is, or was before they went to collectors, a big stack of them somewhere.

“Painting 429” displays the structure consistent to this whole group, and presumably to the larger group implied by the numeration. It’s a horizontal rectangle less than about three feet wide by two feet high, with the Masonite of its support showing as a brown border an inch wide all around.

The dark brown of the Masonite serves several functions. It establishes “429” as an object instead of an illusion, sets its tonal value and to some degree its hue, visually defines is relationship to the others in this group and its larger set, and provides conceptual boundaries for field of action.

The action is the paint, deliberate in a well-defined background that starts with a warm violet-based earth-tone rectangle on the left, a larger, lighter field in the middle, and one that’s nearly pink in the right, all neatly laid down like a solid bass groove.

The melody, changes, and improvisations occur in the central rectangle, as red lines and marks, a black mass, pink shapes, and cloudy whites overlay deep or lighter blues. This is where the painting’s identity lies, where it establishes its individuality. It may be part of a set numbering in the hundreds, but it is its own object, its own presence. Its existence as an individual in a crowd is, and I believe has been for years, central to Manning’s approach.