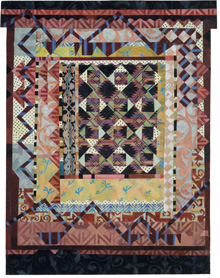

‘KASAYA 3’ Collage on board with hand-printed papers

48 by 63 inches, 2013, by Alice Spencer. |

Drawing artistically on objects of another culture and time can raise highly problematic issues like aesthetic colonialism, unqualified homage, or cynical appropriation. Aucocisco Galleries’ current show touches on all of the above with Alice Spencer referencing ethnic textiles and Heather Perry Victorian mourning jewelry. Ultimately, however, their works’ relationship to its source material is one of conceptual and visual inspiration, resulting in finely crafted art that embodies mature artistic choices and aesthetic independence.

Aucocisco’s show is actually two solo shows. Spencer’s “Kasaya” continues her exploration of patterns with nine complex and colorful collages of stencil-printed paper. Perry’s “The Weight of the Heavenly Garden in the Plane of Existence” comprises four intricate black necklaces mounted on the walls. Between them, the artists’ contributions create a visual balance of weight and busyness across the space.

Spencer has been collecting and studying ethnic textiles for many years. They surface in her work in various ways, the focus shifting between patterns, techniques, and general shapes, such as that of a kimono. Conceptual aspects of clothing and textiles, their function as shelters and markers of cultural identity too have been variously in the foreground. In her current series, named after traditional Buddhist monks’ robes made of discarded fabric, Spencer focuses on the structure of pieced textiles and mostly abstract patterning, using them as points of departure for her collages.

Viewing these intricately composed and layered pieces as reproductions or on computer screens absolutely does not do them justice. Even seeing them from afar foregrounds their overall design, which can appear overwhelming at that distance. It is best to look at the works up-close first and understand their surface and making. That’s when complex design breaks down into individual decisions and their traces, when the collages’ handmade and tactile quality becomes apparent, especially when seen slightly from the side, and when their matte surface appears curiously appropriate for layering pieces of paper of equal weight, even suggesting a modicum of depth. Approaching Spencer’s pieces in this way first becomes revelatory and exhilarating.

Within a vocabulary of geometric patterning, compositional symmetries are constantly broken up and enlivened by directional forces and equivalences of color and weight. For instance, the zigzag bands and triangles overlaying the upper and lower ends of the composition in “Kasaya 3” are not identical, but they project the same bounciness. This is where Spencer’s mastery of form and aesthetic choices shines, particularly when playfully letting a piece’s needs take over, resulting in irregularly shaped but organically grown pieces.

The titles, forms, and materials of Perry’s oversized necklaces wonderfully align to suggest the emotional experience of loss. A title like “The Abiding Ornaments of Your Memory Wrought in the Unbearable Dominion of My Longing” not only echoes 19th-century poetic and verbose writing, but also clues the viewer in to the meaningfulness of the piece’s form. Instead of the black obsidian or jet stone commonly used in Victorian mourning jewelry, which was introduced by Queen Victoria herself, Perry uses a most apposite contemporary material: molded concrete. In this particular piece, an overabundance of black concrete “jewels” cascades from the velvet band around the neck of an imagined wearer, burdening her with the weight of those memories, cultural conventions, and expectations. The decadence and intensity of Perry’s pieces evoke lugubrious Victorian sentiments of thwarted longing, and the viewer may easily feel transported back in history, especially since the necklaces maintain the notion of functionality.