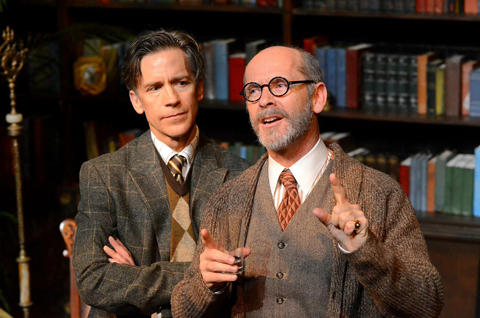

WHO'S THE FOOL? Kneeland and Shea. [Photo by Richard W. Dionne, Jr.] |

Many well-known people visited the dying Sigmund Freud in his last weeks, including Virginia and Leonard Woolf, H.G. Wells, and Salvador Dali. But playwright Mark St. Germain chose to fashion a visit by British writer C.S. Lewis into Freud’s Last Session. 2nd Story Theatre is presenting a brisk two-person imagined dialogue in a trimmed version in their intimate downstairs space (through June 29 and July 24-August 3). It has been pared down to a hair less than an hour from the 75-minute length announced in the program.

Directed by Pat Hegnauer, the knockout production avoids digressions and keeps the interplay punchy, leaving us reeling as well. Think Crossfire on the History Channel.

Lewis was chosen for this last encounter with the man who transformed 20th-century thinking about thought because that paragon of rationalism was an atheist, and the author of The Chronicles of Narnia and The Screwtape Letters was a prominent Christian apologist. Debating the existence of God and an afterlife was an appropriate topic for their conversation, since the devout nonbeliever was going to die in a few weeks, at his own hand, from the oral cancer he’d been suffering from for 16 years.

Ed Shea portrays Freud with the excitement and wit of a man who, at 83, knows he is dying and that his every argument will be one of his last. Wayne Kneeland gives us a Lewis who is supremely self-confident about his faith without losing our respect by being smug. Director Hegnauer choreographs an intricate series of dances between them, from balletic to aggressive tango.

We find them at a moment fraught with tension. The time is 1939 and Germany has just invaded Poland, as a radio reports. Freud and his family have escaped to London. His wife is out shopping for canned goods because bombing is expected to begin at any time. Anna, his daughter and successor in developing psychoanalysis, is brusquely summoned by phone at one point when he is in particularly excruciating pain, but she never arrives.

All the seriousness is frequently leavened by humor, in passing (“Don’t sit there!” Freud says when Lewis is heading for the couch) or elaborately (Christian objections to premarital sex, Freud observes, are “like sending a boy off to play a concerto when the only time he’s had to play his piccolo was alone in his room”).

Freud has invited Lewis because he was interested in a recent essay on Milton’s Paradise Lost, the classic explanation of good and evil in the world. Lewis, 40, had been an atheist into his 30s but is making up time as a dedicated Christian. For his own part, Freud argues that Lewis is seeking God as a search for a perfect father figure to replace his actual, as he put it, “tyrant” father.

That humans might crave a benign afterlife is made manifest by the abject terror of the two men when a glaring air raid siren sends them scrambling in panic for gas masks. The theological clarification is perfect, without a word spoken.