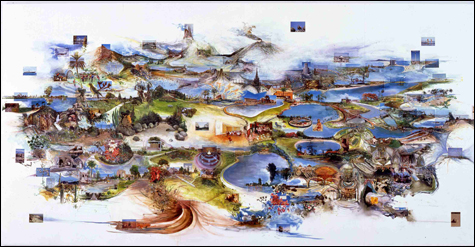

THE TILTED CHAIR (2003): The 16-foot-wide collage represents some of Wegman’s finest work. |

In 1970, William Wegman was making short videos — jumping around in his underwear with purses hanging all over him, that sort of thing. And his new dog, a Weimaraner he’d named Man Ray, after the Surrealist photographer, liked to wander about the edge of the frame. Wegman had become a casual sort of artist, so he left the dog in. Soon the dog became one of the main attractions.

In one video from that time, Wegman crawls backward on his hands and knees spitting a line of milk upon the floor until he disappears behind a corner. Then Man Ray appears from behind the corner licking up the milk until he bumps into the camera. People laughed. Before long, Wegman became known as the artist with the Weimaraner.

The Addison Gallery’s new Wegman retrospective, “Funney/Strange,” organized for the Andover institution by guest curator Trevor Fairbrother, points out that there’s lot more to Wegman than Weimaraners. But I have to report that, with a few exceptions, the Weimaraners remain his best stuff.

Wegman was born in Holyoke in 1943 and studied painting at MassArt (class of ’65). In grad school in Illinois, he quit painting Frank Stella knockoffs and, after a detour as a sculptor, wound up a very serious conceptual artist. It was a very serious time in art, dominated by the puritanical rigor of minimalism and conceptual art. Wegman very seriously flung Styrofoam letters and punctuation marks into a river and tossed plywood shapes into the air while friends photographed him and taped Band-Aids to his face in the shape of the word “wound.”

Like the Addison’s recent shows of Chuck Close and Jennifer Bartlett, the Wegman show traces the way artists in the 1970s left the fundamentalism of minimalism and conceptualism and returned to representation — though they never totally abandoned the faith. For those who weren’t around then, it’s hard to see what all the fuss was about. Young artists today mix and match lavish imagery and minimalism and storytelling and whatever else they desire without thinking twice about it. But back then, in the endgame of high Modernism, that stuff was sacrilege as the avant-garde obsessed over the elemental nature of art. Is a blank canvas art? What happens if you get rid of the canvas? Is an idea enough to be art?

Wegman felt he’d reached a dead end with his minimalist conceptualist works. His “eureka,” as he later called it, came in 1970 when he drew little circles on his hand to match the shape of the stones of his ring before heading out to a party. There he discovered that the circles on his hand matched the peppercorn rings in slices of salami. He dashed home, bought his own salami, arranged it on a plate and photographed his hand, with ring and drawn-on circles, reaching for a slice. Wegman’s way out of his corner, the way out of all that deadly pretentious seriousness, was — ta-dah! — slight punning jokes.