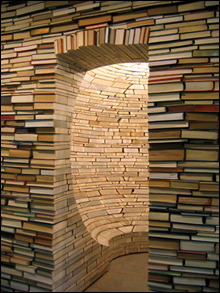

CARVED IN PAPER: A cube of knowledge. |

In the mid-1970s, Dutch artist Nikolaus Urban did an eight-day performance in which he attempted to teach a parrot to speak the last line of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Mathematicus: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” As it happened, at the end, the parrot wouldn’t say a word.

“If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.”

The final words of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus are among the most famous in philosophy, constituting a wonderfully self-deprecating take on the rigors and absurdities of the philosophical enterprise, and an almost heroic staging of the pragmatic implications of the most apparently “abstract” investigations. “He who understands me finally recognizes [the propositions in this text] as senseless,” he writes, “when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it) ... then he sees the world rightly.”

But, as critic Marjorie Perloff has noted, at the very moment that one “sees the world rightly,” one also sees, for the first time, as it were, a set of problems and provocations the surmounting of which demands the employ of additional ladders.

“Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

Aaron T. Stephan’s current show at Whitney Art Works takes this conundrum as its title — which, as Marcel Duchamp once insisted, is the most important part of any work of art. “The Problem with Ladders” — embedded in it is a pair of possible readings. First, most straightforward, and most likely, “the problem with ladders” suggests that using ladders always gets one into trouble, whether or not one accomplishes one’s goal by means of them. Second, less likely, but maybe more obliquely accurate with respect to Stephan’s work: “the problem with ladders” is a purely descriptive title — here is a problem, together with ladders, like a still life together with a violin.

“A picture is a fact.”

In the front gallery, there are seven of them. Pictures, facts: lovingly developed photographs of details of several of the more than 15,000 books Stephan collected over the last year from twenty-three New England library depositories. They are grouped into two enigmatic sets and there’s nowhere near enough information provided to help one determine what relation these different books and their details might bear to one another. From the cover of a worn book, an image of an old farmer in a tunic, holding a sickle, handing the earth to a young boy. An image of the birds pecking at Pinocchio’s nose. A drawing of young Winston Churchill, one guesses, shown walking in the aisle of Westminster Abbey, hat in hand. The observation of the fact of their proximity becomes the only determination one can make: that there is a poetic fact, unintelligible in words, established by the series itself, by itself. Following from this: it is the fact, not the word, that is the unit of poetry.“Philosophy ought really to be written only as a form of poetry.”

At the center of the gallery stands a cube, taller than most people, constructed out of books exhaustively selected and meticulously arranged so that the width of each row is virtually uniform. From three sides it appears impregnable, in every sense. On the fourth side is an entrance, a passage into a spherical room in the structure’s center. Lit from above and with a reading stool in the middle of the circular hole on the floor, one can sit and trace the curve of hundreds of thousands of pages carved seamlessly and attend to nothing but the stationary speed-blur of arrested text peppered with flecks of words at the edges of clean-shaven pages. In here there seems indeed to be nothing whereof one can speak, but the acoustics are too good to remain silent.