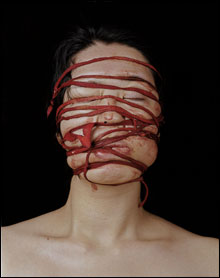

RYOKO SUZUKI, BIND: Is the dispiriting

emphasis on self-mutilation meant to be

empowering? |

“Global Feminisms” at Wellesley College’s Davis Museum could be one of the most important exhibits of the year. It rounds up nearly 80 artworks by 63 women artists born since 1960 from nearly 40 countries to consider the present state of feminist art in the West and provide an overview of some of the cool stuff women are making elsewhere. The spotlight is on a biting critique of sexism and its ugly permutations around the world. And there’s lots of video, a sign of feminist art’s long-time focus on (recorded) performance — something that’s come to have a major place in the art world.

But “Global Feminisms” is a depressing experience. When I first saw it — in March, at the Brooklyn Museum, where it originated — one piece stuck in my head as epitomizing both the best and the worst of the exhibit. Israeli artist Sigalit Landau’s 2000 video “Barbed Hula” shows the artist naked and mangling her belly by hula-hooping with a ring of barbed wire on a beach. “The object of pain,” the catalogue explains, is “a symbol of the geographic barrier created along the West Bank to delineate land between Palestine and Israel.”

At the Davis Museum, which is reopening after more than a year of building repairs, the violence is toned down a bit because Davis curator Elaine Mehalakes gives the art (three-quarters of what was shown in Brooklyn) more room to breathe. But the exhibit still puts a dispiriting emphasis on self-mutilation. In photos, Japanese artist Ryoko Suzuki binds her face with bloody strands of pigskin. In a video, Serbian Milica Tomic claims 30 nationalities while bloody cuts appear across her body. American Mary Coble pastes duct tape to her naked breasts and rips it off till her bust turns an angry red. Spain’s Pilar Albarracín moans and wails through a flamenco tune before stabbing herself in the chest.

That’s not all. Cuban Tania Bruguera straps a lamb carcass to her naked body and eats dirt. Swede Annika von Hausswolff stages crime-scene photos of female rape and murder victims dumped along lonely roads. In a photo, German Claudia Reinhardt re-enacts Sylvia Plath’s suicide, complete with her head stuck in a kitchen oven and a note on table: “Please look after the kids.”

These works have important targets: violence against women, the lack of recognition of female artists, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, jingoism, prejudice against the lesbian-gay-bisexual-transsexual community. They convey the pain of oppression. But grouped all together, the self-mutilation and the self-humiliation feel like sexism turned inward. It’s the opposite of empowering.

“Global Feminisms” was organized by Maura Reilly, curator of the Brooklyn Museum’s new Center for Feminist Art, and her former professor Linda Nochlin, who penned the landmark 1971 essay and call-to-arms “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” The exhibit muses on motherhood, marriage, aging, family, gender roles, national identity, sexuality, pornography, gender bending, racism, and religious-based oppression of women.