Can a striking exhibit at Harvard really make us see ancient Greek and Roman sculpture — and the roots of racism — as we never have before?

By GREG COOK | December 9, 2007

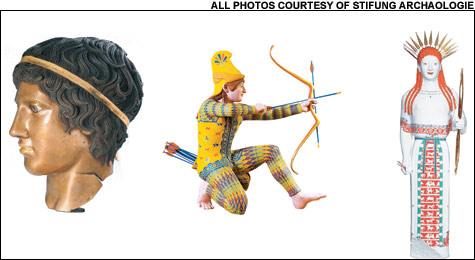

OLD PAINT: (From left) Head of Youth, Roman, early 1st century AD; Trojan Archer from Temple of Aphaia on Aegina, Greek, c. 490–480 BC; “Peplos” Kore, Greek, c. 530 BC. |

The Parthenon in Athens, Rome’s Pantheon, and the great naturalistic sculptures of ancient Greece and Rome have stood for centuries as emblems of the heights of Western culture. Even in ruins, they’ve represented pinnacles of beauty, simplicity, and humanism. Might our understanding of these familiar stone monuments not only be mistaken, but also harbor a racist legacy?When we think of the ancient Greeks and Romans, we picture them among the sober silent white stone of their surviving sculptures and columned temples. But the exhibit “Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture in Classical Antiquity,” at Harvard’s Sackler Museum, presents striking evidence that our sense of ancient sculpture is distorted because we’ve forgotten that the white marbles were once painted in bold Technicolor.

Based on two decades of detective work by German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann, here some 20 plaster replicas have been painted to approximate the ancient sculptures’ original appearances. The look is disconcertingly garish. Vivid red, blue, and green scales cover a Greek warrior’s helmet. A funerary monument for another warrior depicts him in yellow-leather armor decorated with blue stars and a green and yellow lion’s head. All this color feels wrong, wrong, wrong. And it’s this visceral reaction that makes the exhibit so intriguing.

“In the study of ancient art there is scarcely any area so much shrouded in mystery as the coloring of the temples and sculptures,” Brinkmann writes in the catalogue. “Since the artistic works achieved their real and intended effect by means of coloring, this also means a serious loss in understanding of them.”

Our notion of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture seems to originate in the Renaissance. Europeans made painted sculpture up through the medieval, Romanesque, and gothic periods. But around the 15th century, as the Renaissance dawned, artists and leaders sought inspiration in ancient Greece and Rome. These civilizations were seen as heights of culture — as well as heights of power — that artists and rulers emulated. Renaissance discoveries of ancient Greek and Roman marbles with their paint worn off by centuries of exposure to the elements (and then cleaned) inspired the great unpainted marbles of artists such as Michelangelo — and centuries of sculpture that followed.

Still, it’s not exactly news that the ancients painted their sculptures. In fact, research into painted classical sculpture goes back at least 200 years. Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts even presented an exhibition on painted classical sculpture more than a century ago, in 1891. And the brilliant colors employed by ancient cultures are apparent on surviving glazed-brick-wall reliefs from ancient Babylon (in present-day Iraq) and dazzlingly ornate coffins and statues found in the tombs of ancient Egypt.

Related

Related:

A new Gardner, plus landscapes, performance art, and RAD, Cannonball quiets Harvard quad, Slideshow: Record Hospital Fest 2009, More

- A new Gardner, plus landscapes, performance art, and RAD

Greater Boston's art-museum building boom continues with the debut of an expanded Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in January.

- Cannonball quiets Harvard quad

It’s been awhile since we had to worry about the multi-colored national danger spectrum, but last week, the northwestern quadrant of Harvard Square was put on high alert.

- Slideshow: Record Hospital Fest 2009

Record Hospital Fest 2009 at Harvard's Holden Chapel, April 11

- Quiz-bowl kids

Andrew Watkins is having faulty-buzzer issues.

- Free speech again quashed at Harvard

It should come as no surprise to readers of “Freedom Watch” that yet another instance of political, intellectual, and academic censorship has sprung up at Harvard, the self-touted pinnacle of higher education.

- Harvard virginity conference pops its cherry

At what moment are you no longer a virgin? When you get a blowjob? Give one? Give 30 ? When someone fingers you? Oral sex? Anal sex? Enjoyment? Orgasm?

- Ledge Lessons

As advocates of higher education and living as long as medically possible, we were sad to read that, according to new-media-powerhouse Web site the Daily Beast, Greater Boston is home to not one but five of the most stressful colleges in the United States.

- Mr. Populist?

Barack Obama is an inspirational leader, a potential realigner, and a racial trailblazer.

- Long-lasting launch pad

Of the nearly 70 ballets that made up the repertory of Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, only a few inhabit our stages today. But the Diaghilev adventure still inspires legions of choreographers, antiquarians, archivists, scholars, and gossips.

- The Gates case isn't about race

The weeks-long hubbub over the arrest of Harvard professor Henry Louis "Skip" Gates Jr. by the Cambridge Police Department has centered on race, understandably, for two reasons: 1) the African-American population has suffered inequitably in its relations with law enforcement across this country, and 2) a race story is easier for the media to tell — and to sell.

- Sweeping up

Whether by design or dumb luck, Governor Deval Patrick has managed to depoliticize the news coming from Beacon Hill.

- Less

Topics

Topics:

Museum And Gallery

, Science and Technology, Archaeology, Harvard, More  , Science and Technology, Archaeology, Harvard, gods, Sackler, museum, Roman, Greek, racism, classical, Less

, Science and Technology, Archaeology, Harvard, gods, Sackler, museum, Roman, Greek, racism, classical, Less