All it took was one rash “late merge” to inspire Tom Vanderbilt to write his tome on traffic. (He flouted “lane ending” signs till the last second, then barged his way into the adjoining still-open lane.) For days post-late-merge, Vanderbilt had feelings of guilt and confusion. Was what he’d done so wrong? He went on-line to Ask MetaFilter and drew plenty of riled-up responses. Fans of fairness proclaimed the righteousness of queuing up and waiting your turn; fans of physics cited the practicality of using all available space for maximum efficiency. That clash of opinions got Vanderbilt to thinking about how people’s attitudes toward driving reveal a lot about psychology and culture.

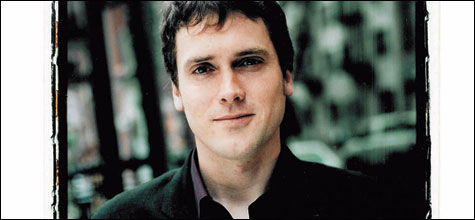

Vanderbilit has written for the New York Times, Slate, Rolling Stone, and a long list of other familiar titles. In a previous book, Survival City, he visited fallout shelters and other Cold War–era buildings to examine what it meant to live with a constant sense of vulnerability. In Traffic, he looks at what it means to go careering down the highway with no sense of vulnerability whatsoever. It’s more complicated than that, of course, but he does have some good ideas about our misguided approach to driving, some of them counter-intuitive, some not. To live longer, don’t drive on rural non-interstates. To be safer, jaywalk. To remain alive around 18-wheelers, don’t drive like a dope.

Vanderbilt asserts that “traffic culture can be more important than laws or infrastructure in determining the feel of a place.” In the ’60s, the ever-progressive Netherlands invented woonerven (“living yards”) in small towns. Woonerven have no high sidewalks, traffic signs, or crosswalks, but plenty of trees, flowerpots, cobblestones, and fountains. The boundaries between the worlds of pedestrian, bicyclist, and driver dissolve. Yet cars can’t go faster than walking speed (5 to 10 miles an hour), so, no surprise, the roads are safer.

Many of Vanderbilt’s findings are similarly unsurprising. Everyone considers himself/herself to be an “above-average” driver. SUV drivers are more apt to drive aggressively, yak on cell phones, and speed. Maybe that’s because they’re higher off the ground and don’t realize how fast they’re going.

Or maybe SUV drivers tend to be jerks, and maybe we’re just plain cocky about our imaginary driving skills. But Vanderbilt is not one to judge, sometimes sticking to the scientific approach beyond the point of logic. At length, he ponders the differing ways we choose parking spots and draws analogies to animals’ hunting strategies. Isn’t it possible that we spend forever looking for a great spot because we’re l-a-z-y?

Vanderbilt can’t be accused of going half-hog. He consults hundreds of experts, most of whom speak as theorists rather than drivers. Traffic is weighty enough that you could use it to conk a rude driver. But it might’ve been more rousing if Vanderbilt had included the voices of actual drivers. It was, after all, their seething responses to his late-merge question that inspired him to write the book in the first place. Without their voices, relevant questions remain unasked. Why do you feel compelled to rush into an intersection to create gridlock? Why do you, when you enter a highway, think you have the right of way? Are you unmindful? Rude? A typical American asserting your individuality?

Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (And What It Says About Us), by Tom Vanderbilt | Alfred A. Knopf | 414 pages | $24.95