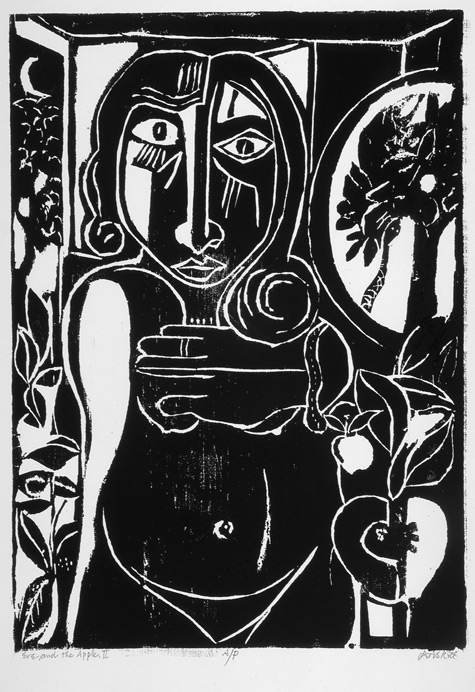

SHOWING DEVELOPMENT “Eve and the Apple II,” by David Driskell, circa 1968. |

For more than 50 years David Driskell, in his art and his distinguished academic career, has been a creative force in the intersection of modernist art and the African diaspora. An educator, painter, sculptor, author, and curator, he has also been an active printmaker. “Evolution: Five Decades of Printmaking by David C. Driskell,” a collection of some 80 works executed between 1952 and 1997, has recently been installed at the Portland Museum of Art, its last stop on a national tour.

There’s a sense, in much of Driskell’s work in this show, of a spiral of influences that turns back on itself. His work is deeply embedded in the modernist ideas that grew out of the work of Picasso and Matisse and the others, which in turn took much of its inventive energy from African art they saw in Paris.

This circling path is apparent in, for instance, the hand-colored woodcut “Eve and the Apple III,” where the figure’s face recalls Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” which itself got its inspiration from African figures. The iconography is Christian myth, the structure is modernist, and the colors reflect African textiles.

The figure in the woodcut “Reclining Nude” gets its posture from Matisse. The various versions of “Bakota Girl” relate directly to Kota sculpture and to Cubism, and one version, “Bakota Girl I,” combines all that with the feeling of a quattrocento depiction of the virgin Mary.

There’s more, though, to the artist’s life and accomplishment than just the influences, which in Driskell’s work simply point toward the breadth of his vast learning. Prints, which are at least one step removed from the direct action of the artist’s hand, sometimes possess, paradoxically, a special kind of intimacy. Because there are so many in this show, and because they cover such a long time-span, the attentive visitor has a detailed look at how his thinking has evolved over the years.

There’s the tentative but forceful young man with his wife in 1952 in “School Life, David and Thelma” surrounded by the artifacts of his education. The show demonstrates that even as his work quickly moved away from academic realism he continued to populate his images with icons that flesh out the narrative surrounding the subject.

It’s a mistake to assume an inevitability to a retrospective look at an artist’s history. The free sure hand of the lithograph “Night Owl,” from 1956, seems, looking back, to have developed quickly from the rather stilted earlier “School Life” piece, but I suspect the ease demonstrated in the later was hard won.

By the mid-’80s Driskell was using an all-over pattern in which the pictorial intensity and focus is maintained at the same level across the whole piece. In “Spirits Watching” the faces and hands exist at the same pictorial level as the vivid color areas that fill the piece. In a related piece, “Ancestral Images: The Forest,” the figures are layered onto a set of vertical stripes. Again, he reflects developments in American painting and brings them into the concerns that have occupied his whole career.

Some of the later works seem almost to go back to an earlier time, as if he were sensing the arc of his career and revisiting parts of it. The recent woodcuts “The Bride,” “Deer Isle,” and “Self-Portrait” seem somehow to be younger, even as the portrait reveals his maturity.

It is in the nature of a retrospective to reveal the processes and changes that an artist goes through in a career. This show does more than that. Its intimacy opens a window on the nature of Driskell’s character and temperament. It is a measure of his confidence that he is willing to share as much as he does.