|

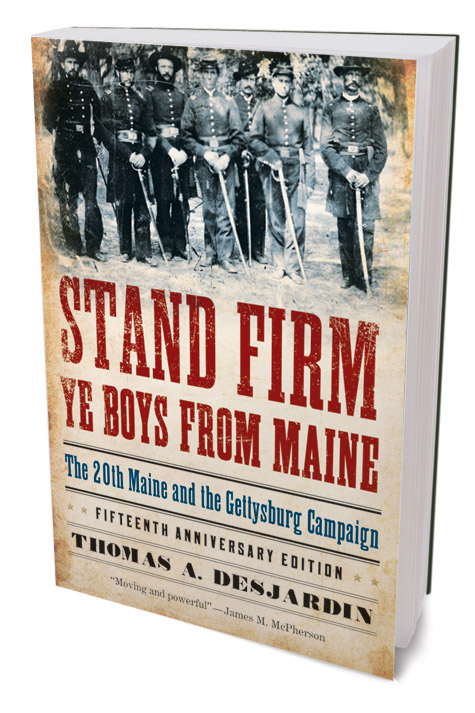

The soldiers of the 20th Maine Regiment marched quickly into the night, moving west from Hanover toward Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1863. They'd received word that it had begun, the fight that could determine the outcome of the Civil War. Rumors flew as they hurried toward the fighting. Had George McClellan replaced George Gordon Meade as leader of the Army of the Potomac? Had he replaced the commander of all Union forces, Henry Halleck? Was the ghost of George Washington (who'd been dead more than 60 years) in Gettysburg? These were the realistic and outlandish questions in the men's minds as they prepared for their part in what was to be the most significant military engagement ever to take place in the Western Hemisphere. And these psychological details are what make Thomas Desjardin's Stand Firm Ye Boys from Maine (being reissued this month on its 15th anniversary), a definitive account of the battle about which countless reports, books, and visual depictions have been rendered.

Desjardin, himself a Mainer, presents a historian's passionate narrative of the drama and routine of the ordinary soldier's life. Using first-hand accounts, popular and scholarly history, and references to historical fiction, he recounts what is known to have occurred in the crucial fighting on Vincent's Spur of Little Round Top, what is thought to have occurred, and what will never be known with certainty. Sympathetically (the odds against them were great), he portrays William C. Oates and Michael J. Bulger, commanders of the 15th and 47th Alabama regiments, and their courageous men who assaulted the 20th Maine's positions. And he treats in great detail the thoughts and actions of Maine native and Civil War legend Joshua L. Chamberlain, his captains (most notably Ellis Spear), and the 500 officers and enlisted.

Through the story of one military engagement, Desjardin illustrates overarching themes such as how the poignancy of war lies in the juxtaposition of bravery and tragedy, and how legends evolve over time.

Many things lined up to create the mythology of both Little Round Top and Chamberlain, and Desjardin outlines them carefully. Among them, if generals Buford and Reynolds had not blocked the rebels from taking the high ground south of Gettysburg on the first day of fighting, Little Round Top would not have happened. And if Pickett's Charge had succeeded on the third day, Little Round Top would have become a footnote.

Meanwhile, if Chamberlain had not been such an unlikely commander — fluent in several languages, highly literate, and a philosopher — he may not have achieved such a heroic status. His contradictions made him relatable, as a fighter then, and as a historical figure later on. Desjardin paints a nuanced picture of Chamberlain, who went on to serve as governor of Maine, Bowdoin College president, and then surveyor of the port of Portland. He writes of a human hero who was insecure in his relationship with his wife. And he points out that Chamberlain's tactical maneuver at Little Round Top — the legendary bayonet charge, which saved the day, and the Union's left flank — was reckless. Reckless, successful ventures have a way of staying with us.