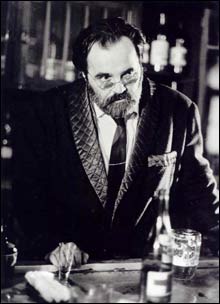

DAMNATION: Some of the most magnificent black-and-white images shot anywhere in the world. |

It was only with DAMNATION (1988; January 12 at 6:30 pm + January 17 at 9:15 pm), and Tarr’s interface with acclaimed Magyar novelist László Krasznahorkai, that things became recognizably Tarrian. This small-framed film — modest at least relative to the subsequent epics SÁTÁNTANGÓ (1994; January 12-13 at 2 pm) and WERCKMEISTER HARMONIES (2000; January 12 at 8:45 pm + January 17 at 6:30 pm) — traces the self-destructive lives of two men and a weary bar chanteuse in a dead mining town where anomie and liquored exhaustion infect their lives like a virus. As shot by Tarr comrade/superhuman cinematographer Gábor Medvigy, it’s a serotonin-depleted ordeal, and something of a lovely sketchbook of vibes and ideas to come, with some of the most magnificent black-and-white images shot anywhere in the world.Considering Krasznahorkai’s role in the creation of Tarr’s most famous films is a dicy maneuver — as is any prognostication pertaining to who’s responsible for what in a collective project we didn’t witness. Damnation, for instance, began not as a novel but as a screenwriting collaboration between the two men, at a time when Krasznahorkai had published only two novels (the first of which was Sátántangó). Only the later novel and the source for Werckmeister Harmonies, TheMelancholy of Resistance, has been translated into English, and by the look of it the author’s prose approach is more matter-of-fact, more internal and ruminative, and more historical. There’s no hint of the solemn, monumental, nearly abstracted poetry that we see in Tarr, and though Krasznahorkai’s sentences are rich and ropy, much of the novel’s political material and specific social commentary goes missing in the film. A single descriptive page can turn into a monumental 12-minute set-piece in the Tarr film, minus its psychology and real-world context but plus an unforgettable saturation in space and time. All the same, you could hardly nail it down as a case of a crazed cinéaste mutilating a novelist’s vision — Krasznahorkai co-wrote the screenplays, and the film of Sátántangó, for one, took many years for the impassioned partners to get produced. We can assume that the metamorphosis from book to film was understood by the writer as a crafting of a new and radical art object, beside which the novels independently sit, retaining their own, very different form and voice.

Vetting these probabilities is of little use to you if you haven’t experienced Sátántangó, because it is first and foremost an experience, a seven-and-a-half-hour ordeal by shadow in which the passage of time upon the eyeballs is its very raison. Like the films of Jacques Rivette (the HFA is thinking l-o-o-o-ng this winter), Sátántangó is a vast lake you explore for its endless depth, not a narrative river you ride from plot point A to point Z. It’s been said that two-hour slices could stand as redoubtable films on their own, but one shouldn’t be thinking it’s a Dr. Zhivago–style epic. (The novel is modestly sized.) Rather, it’s an epic trance state, a massive portrait of a withered universe. (Virtually any frame of Medvigy’s celluloid is a framable work in its own right.) Set entirely in a rainy, desolate village fallen into inertia after the collapse of its collective farm, as well as on the surrounding flatland puszta, the film details the lives of the peasants as they await settlement money for the land — money about which they are in a constant state of anxiety. Goldbricking is on everyone’s minds, particularly once it’s rumored that a well-known grifter everyone thought was dead is going to return — from the grave? — and doubtless scam everyone out of his or her share in order to keep the dead dream of Communism going.

Related

Related:

Once upon a time in Hungary, Review: The Man From London, Wish-fulfillment for a burning world, More

- Once upon a time in Hungary

Since its release in 1994, Hungarian auteur Béla Tarr’s 435-minute sui generis masterpiece Sátántangó has had the top critics grasping for superlatives.

- Review: The Man From London

I had to wonder whether this latest film from Béla Tarr (co-directed by Ágnes Hranitzky) is a self-parody.

- Wish-fulfillment for a burning world

From the shining big-screen debut of Iron Man to the large amounts of green produced by the Incredible Hulk, this was the year the public couldn't get enough of their favorite heroes.

- Cinema of suffering

Film, like most arts, tries to turn misery into entertainment.

- Fallen

Drain Blow-Up of its psychedelic hues and manic outbursts and you’re imagining Fred Kelemen’s darker-than-noir existential mystery.

- Kino pravda

Because Mosfilm, the subject of the Museum of Fine Arts’ “Envisioning Russia” retrospective, was the Soviet state production studio, any cross-section of its history lays out the entirety of Soviet film history.

- Doing time

It's not so much about killing as it is about time. Horror scope: Robert Graysmith’s Zodiac obsession. By Peter Keough

- Tilda Swinton's mixed metamorphoses

Most people know Tilda Swinton either from her role as the White Witch in the Narnia movies or as the striking-looking woman who in her speech accepting the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance in Michael Clayton said she was going to give the trophy to her agent. Or perhaps as the actress whom Conan O'Brian said he would like to portray him if there's ever an HBO movie made about his life.

- Less

Topics

Topics:

Features

, Jacques Rivette, Andrei Tarkovsky, Theo Angelopoulos, More  , Jacques Rivette, Andrei Tarkovsky, Theo Angelopoulos, Bela Tarr, Laszlo Krasznahorkai, Alexander Sokurov, Mikhail Kalatozov, Less

, Jacques Rivette, Andrei Tarkovsky, Theo Angelopoulos, Bela Tarr, Laszlo Krasznahorkai, Alexander Sokurov, Mikhail Kalatozov, Less