Arthur Penn at the Harvard Film Archive

By STEVE VINEBERG | January 29, 2008

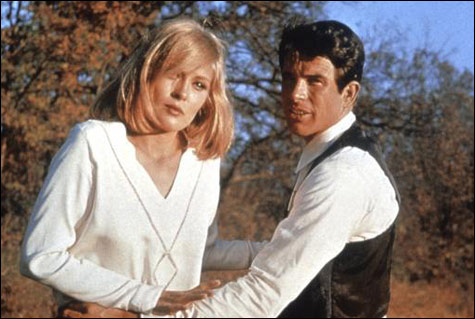

BONNIE AND CLYDE: The great American film renaissance began with this one. |

During the great American renaissance period in movies, Hollywood was in the hands of the counterculture, and filmmakers, many of them trained in the theater or under the hothouse pressures of live television, and excited by the modern classics that had come out of Europe in the ’60s, experimented with the conventions of movie genres. It all began in the fall of 1967, when Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, the first gangster picture with complex, sympathetic heroes, divided the critics (many found it morally repugnant) but made an immediate and deep connection with young audiences. They were entranced by its interplay of glamor and contemporary put-on humor, its tonal shifts, its take on the topics of celebrity and role playing, its realistic depiction of violence. Bonnie and Clyde opened the fall of my senior year of high school, and the following Monday morning it was the only thing my classmates and I could talk about. Everyone had seen it or had made plans to. My first college girlfriend told me that the weekend it opened in her town she saw it two nights in a row.

Penn flamed into the front ranks of American directors with the film’s release, so it’s easy to forget that at that point he already had a career. The fascinating Harvard Film Archive series “Arthur Penn, American Auteur” pays tribute to his early days as well as to the decade that followed BONNIE AND CLYDE (Sunday at 7 pm); it even includes one of his early television dramas, THE TEARS OF MY SISTER (Friday at 7 pm), from 1953. Penn divided his time between New York’s TV studios and the Broadway stage, and those turned out to be his entrée to Hollywood. In 1962 he brought the William Gibson play THE MIRACLE WORKER (Monday at 7 pm), which he’d directed in New York, to the screen along with its original actresses: Patty Duke as the young Helen Keller and Anne Bancroft as her teacher, Annie Sullivan. His days in TV had taught him how to harness the energy of live performance for the camera: the electric performances of the two stars make Gibson’s stripped-down dramatic text, a triumph-of-the-spirit drama about how a great teacher leads a soul locked away by blindness and deafness into consciousness, into an unforgettable emotional experience. Bancroft and Duke walked away with Oscars, and Penn had a new career.

Topics

Topics:

Features

, Paul Newman, Billy the Kid, Gore Vidal, More  , Paul Newman, Billy the Kid, Gore Vidal, Melanie Griffith, Paul Mazursky, Warren Beatty, Celebrity News, Entertainment, Movies, Richard Nixon, Less

, Paul Newman, Billy the Kid, Gore Vidal, Melanie Griffith, Paul Mazursky, Warren Beatty, Celebrity News, Entertainment, Movies, Richard Nixon, Less