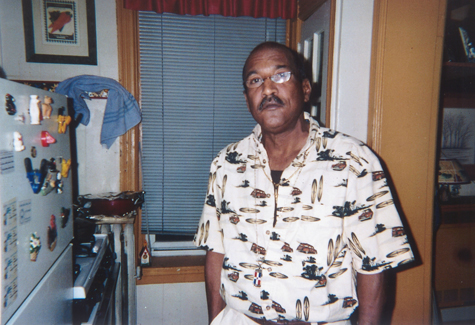

PHOTO COURTESY OLGA RIVERA |

Joking among themselves, a small group of guards entered Close E pod.

"Lock up!" one of them suddenly commanded the prisoners: go to your cells.

Somewhere in the Maine State Prison a correctional officer had forgotten to turn off his portable phone. When this occurs, the prison's computerized control system automatically sounds an alarm. "Off hook" alarms are common and usually meaningless.

Victor Valdez, a middle-aged immigrant from the Dominican Republic who was disorderly in the outside world but quiet and well-liked among Close E's 56 inmates, either didn't hear or understand the command, according to several of his pod mates. He didn't understand English well, and he may have been hard of hearing.

Some prison guards, however, expect inmates to jump when they give an order. The fact that Valdez didn't jump would have fatal consequences.

It was close to lunchtime on November 19, 2009, and Valdez had been using the day room's microwave to heat food in a bowl. He took his food from the oven, set it down on the counter, and grabbed some paper towels so he could hold the hot bowl to take it to a table.

But at that moment a sergeant decided Valdez was disobedient. He angrily ordered him "tagged in," locked in his cell — without his food. When the all-clear came, a prisoner asked permission to give Valdez his food. He was denied.

Next, as punishment for his disobedience he was told he would be put in the "supermax" unit's solitary confinement for 30 days. In response, Valdez became "real loud," according to pod mate Luis Pabón.

"Then they took him away," Pabón wrote to the Phoenix.

That afternoon another of Valdez's pod mates, Franklin Higgins, happened to be in the infirmary for his diabetes testing. He wrote to prison-issues activist Judy Garvey that he saw Valdez, hands cuffed behind his back, being dragged into the unit. Two big officers — Valdez was small — "had an arm up under Mr. Valdez with a hand on his shoulder." He had trouble walking because of the "excessive force" they were applying to him, Higgins said. And Valdez "had blood all over his left arm and back, which was very fresh."

"What did I do?" Valdez repeatedly asked the guards, Higgins said. "What did I do?"

Whatever answer may have come, nobody is saying. The Maine Department of Corrections did not respond to a request to make prison staff available for interviews on the subject of Victor Valdez. Citing the "confidentiality" of prisoner information, officials earlier had refused interviews with prisoners about Valdez — and did not respond to a recent request. The picture presented here largely comes from letters from inmates. But they tell a consistent and tragic story.

A dire prophesy

Valdez was well acquainted with the infirmary. He was a very sick man. His kidneys had failed, and he had required dialysis treatment several times a week for eight years, via a stent implanted in his arm. He also suffered from congestive heart failure, cirrhosis of the liver, and lung problems, according to court documents filed prior to his sentencing in 2009 to four years' incarceration for a 2008 aggravated assault in Portland, where he had lived alone in a Congress Street apartment building. While at the prison, which is in the coastal village of Warren, he received his dialysis at Miles Memorial Hospital in Damariscotta.