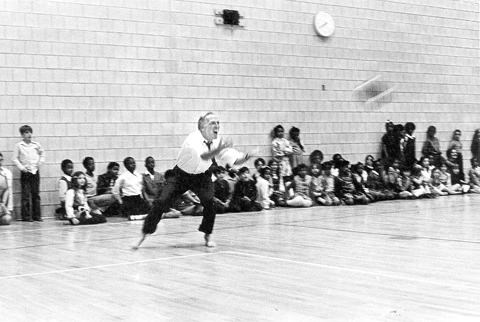

A MAYOR IN LOVE WITH HIS CITY Mayor Kevin White visits a public school. |

Tuesday's Parkman House wake on Beacon Hill for former Boston Mayor Kevin H. White, who died last week at age 82 after a long struggle with Alzheimer's disease, was more than a tribute to the colorful and resilient politician who led the city during historic years of downtown rejuvenation and racial strife.The wake was a belated celebration of the Irish-Catholic Democratic culture that reached its zenith during White's 16 years in office, but which began to decline even before White left office in 1984.

White, like his fellow Democrat, President John F. Kennedy, and Republican conservative ideologue William F. Buckley, was a member of the Irish-American ascendency. For this generation, an elite undergraduate education — Harvard for Kennedy, Yale for Buckley, Williams for White — tinctured their careers with the perfume of the establishment.

While at heart these men never lost their ancestral taste for a good street fight, their public behavior had more in common with Teddy or Franklin Roosevelt than James Michael Curley.

The Irish dominated Boston politics since 1909, when Kennedy's maternal grandfather John Francis "Honey Fitz" Fitzgerald beat Yankee James Jackson Storrow in an epic battle for mayor. But the persistence of class conflict with the upper-class Protestant power structure did not to fade until the 1950s.

During the '50s and into the '60s, good-government Mayors John Hynes and John Collins — technocrats, not backslappers — lowered the temperature of public life.

With White, drama returned.

For most of his mayoral career, White was the candidate of middle-class aspiration. White was more than a politician; he was a symbol.

To those already in the middle class and to the far larger number of blue-collar families aspiring to that status, White validated the idea that social and economic mobility was real. A vote for White was a subliminal endorsement of the idea that each generation could expect to better itself.

In contrast, White's mayoral rivals, School Committeewoman Louise Day Hicks and City Councilor Joseph Timilty essentially defined themselves by not being Kevin White. Hicks and Timilty offered no vision.

White was more than a dash of flash; he was political muscle in a J. Press suit.

"His blue eyes grabbed you, his wry smile roped you in, and his quick mind sealed the deal," said Phoenix founder and publisher Stephen M. Mindich, one of a platoon of Bostonians who shared White's belief that the arts were central to regaining a place on the international map.

Hynes and Collins did the spadework of rejuvenation. They laid the foundation for the tremendous downtown resurgence over which White presided: more than 50 downtown projects in 16 years.

White's most visible physical legacy was to push renewal toward Boston's then-sinkhole of a harbor. The rejuvenation of the Faneuil Hall marketplace was White's jewel, drawing Disneyland-size crowds in its heyday.

Despite presidential ambitions, White never broke out of the cocoon of Boston politics. It was not, however, for lack of trying.

In 1970, three years after assuming the mayoralty, White won a bruising four-way joust for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination.

Those were the days when the state GOP was still a vibrant force. White lost to Republican Francis W. Sargent, perhaps the most likeable politician of his generation.