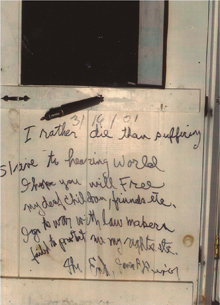

On March 16, 2001, James Levier, a deaf man, took a deer rifle to the Shop and Save parking lot in Scarborough. There, he initiated a stand-off with police, which ended with Levier shot dead. Writings on his van — and on the door of his home — indicate that Levier was despondent over his fear that the administration of then-governor (and current US Senate candidate) Angus King would not fund the Baxter Compensation Authority, a proposed state agency charged with paying reparations to students who had been sexually and physically abused at the Governor Baxter School for the Deaf.

Days later, King pledged his support for the BCA, which eventually received — and paid out to victims — $17 million in state funding from both the King and Baldacci administrations. In Maine's small deaf community, a perception arose that without Levier's final, desperate actions, their years of suffering would have once again been swept under the rug.

Eleven years later, while that feeling still exists in some quarters, not everyone agrees.

Yellow Light Breen, the King administration's spokesman for the Department of Education, says Levier's death affected the process, but perhaps not the ultimate outcome.

BY HIS OWN HAND James Levier left notes explaining his actions; investigators photographed them after his death. |

"There's no question that James Levier's death elevated this issue to a very high degree of visibility for the Legislature. I don't know that means that the compensation program would not have moved forward anyway. There were a lot of passionate supporters of the idea, even before the shooting," Breen says. "I don't think that anybody in leadership positions or in public policy in Augusta was under any illusions about the horrific nature of the abuse that had gone on at Baxter."In fact, according to Breen, the King administration asked him to testify neither for nor against the proposed bill at a legislative hearing (the testimony that set Levier on his final path) specifically because King and others understood the severity of the crimes that had occurred on Mackworth Island. (See "Why I Hate Mackworth Island," by Rick Wormwood, June 4, 2004.)

"Having sat through and read through all of those reports from 1982, and subsequent accounts, I knew how extensive the abuse was, and I knew the Legislature needed to be prepared for this to be a really sizable program, and not to minimize (the potential costs) in the process of getting it passed," Breen recalls. "So we sounded a cautionary note, neither for or against (the BCA bill), but we certainly never disputed the moral imperative of righting the wrong, and we certainly never disputed the conceptual merits of the proposal."

Meryl Troop, a longtime coordinator of deaf services for the state who now works for the Maine Center on Deafness, feels that the Baxter Compensation Authority truly helped Maine's deaf people, and not just with the cash settlements.

"Do not overlook the mental-health services that were authorized for any former student that claims they were abused there," Troop says. "That is still in existence, even though the Compensation Authority has finished its work. So, is the community healthier after ten years of access to mental-health counseling, with no out-of-pocket expense, delivered by people fluent in sign language? Yes, definitely."