NETOCRACY Harvard's Yochai Benkler tracked the spread of anti-SOPA agitation across the Web,

from tech blogs to Anonymous. |

The bills, designed to choke off online piracy of movies, music, and pharmaceuticals, seemed greased for passage.

Hollywood had put its considerable political muscle behind the measures, known by the acronyms SOPA and PIPA. And the legislation enjoyed strong, bipartisan support in Congress.

But Silicon Valley and Internet freedom advocates feared the bills were so ham-handed, so poorly conceived, that they would cripple the Web's open architecture and stifle innovation. And on January 18, they spoke.

Reddit went dark. Google blacked out its logo. And the English-language Wikipedia disappeared from the Web: "Imagine a World," the site intoned, "Without Free Knowledge."

The Internet just about blew up that day: millions of tweets and e-mails and phone calls littering Washington and, in a matter of hours, smothering bills that seemed destined for the president's desk just a few days before.

Observers immediately asked what it all meant: was this a fundamental shift in the political order? Or was it just the spasm of a potent, one-off coalition that was unlikely to repeat itself: the lefty netroots and libertarian right joining with a tech sector staring down an existential threat?

It is, arguably, the single most important question in American politics; after all, if the Internet can obliterate the forces of money, insider influence, and partisanship with the click of a mouse, then the game is utterly changed.

There were no definitive answers in the immediate aftermath of the SOPA implosion. But four months later, a few tentative conclusions are taking shape.

MAPPING SOPA

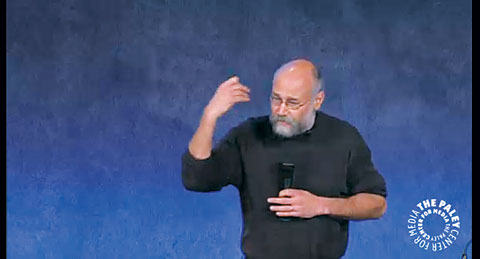

A few weeks ago, Yochai Benkler, co-director of Harvard University's Berkman Center for Internet and Society, stood before a small audience at a conference in New York, clicker in hand. On screen, his latest research: a sprawling map of the SOPA story's travel across the Internet.

It is, he said, a tale of how the "networked public sphere" really works; the Internet, he argued, is not just 80 go-to sites that serve as news filters, it is something far more complex and dynamic.

Indeed, Benkler's map suggests the SOPA story spread with little to no involvement by the mainstream press — starting with West Coast tech media in the fall of 2010, migrating to bloggers in the spring, and taking off in November 2011, when advocacy group Fight for the Future organized American Censorship Day, a potent precursor to the January blackout.

Along the way, there were all sorts of clever interventions. Holmes Wilson, a founder and co-director of Fight for the Future, says the key to Censorship Day's success was putting the sort of "contact your congressman" widgets that have long populated the activist Web on high-traffic sites like reddit and boingboing.

And Tumblr developed a design trick that would soon be adapted by the broader anti-SOPA alliance: redacting user-generated content, in the style of a censored document, to drive activism.

But it seems unlikely that the big Internet companies would have developed these tools — or participated in a political protest of any kind — if the future of the Web, itself, was not at stake.