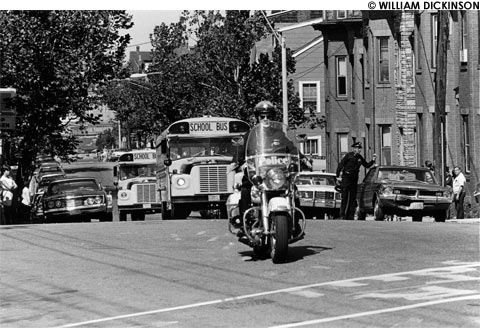

Court-ordered busing, 1976 |

Between now and the end of the year, Boston will wrestle with one of the most important policy decisions it has faced in years: reinventing the 23-year-old system used to assign 56,000 public-school students to 129 schools.

Students, parents, and guardians are obviously the core constituency. But you do not need to be a client of the school system to have a stake in how this shakes out. One way or another, every resident, every business, every taxpayer will be affected.

The city spends about half its budget — $1 billion a year — on education. A little more than $80 million of that is spent on transportation, busing students to and from school. That is more than double the national average.

Years of strenuous efforts to improve Boston's largely substandard schools have yielded consistent but still only incremental changes. That means too many students are bused at great expense to too many struggling schools.

Add to the equation the issue of unproductive time spent in transit, and the result is a system that literally spends too much energy and effort spinning its wheels.

The school department is considering five different plans developed by outside consultants to overhaul the current system. The common denominator of each plan, however, requires the city be divided into a specific number of zones.

At the moment, the system is divided into three districts. By multiplying the number of zones, planners hope to move the system closer to the increasingly popular ideal of neighborhood schools.

Last week, a self-convened group of six elected officials — City Council members John Connolly and Matt O'Malley, and State Representatives Linda Dorcena Forry, Nick Collins, Ed Coppinger, and Russell Holmes — unveiled a sixth proposal, which would allow all students a chance to stay in the schools they now attend, or opt instead for a guaranteed seat in one of four schools nearest where they live.

In a move to balance the convenience of neighborhood schools with the allure of different opportunities, this sixth plan would establish 16 magnet schools with an array of specialized programs throughout the city, to which families could apply via lottery.

Groups of two to six families would be able to band together for guaranteed assignment to less-popular schools. The idea is that this element of choice would spark a family commitment to work with teachers and administrators at such schools to improve quality and performance.

In a city where obstruction and negativity are too often the norm in the political process, this multi-pronged approach is a welcome development.

Mayor Thomas Menino, the school department, and the six officials proposing the "sixth way" plan are bending over backward to be respectful of each other, and have pledged to work together to fashion the most advantageous solution to remaking school assignments.

Mandatory school busing came to Boston not quite 40 years ago as a result of a federal court order that found the school system undeniably racist, with less money being spent on black students than on white students.

Today, Boston is a city where minorities are in a majority. The school population is 42 percent Latino, 35 percent black, 13 percent white, and 8 percent Asian. Racial balance is not the issue. Quality of education is.

Connolly and Co.'s sixth way may well be the most promising way to reset the schools.