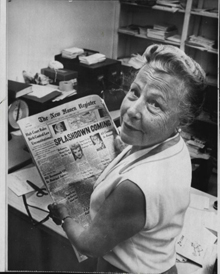

CHANGE AGENT Estelle Griswold was executive director of Planned Parent-hood in New Haven, CT |

Action Speaks, the panel discussion series at Providence art space AS220, continues its fall season October 24 with a discussion of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the landmark Supreme Court decision that overturned a law banning contraception and found a right to privacy in the Constitution, paving the way for the Roe v. Wade (1973) ruling that legalized abortion.Scheduled panelists include Naomi Rogers, a professor of the history of science and medicine at Yale, Heather Munro Prescott, a history professor at Central Connecticut State University, and Susan Brison, chair of the philosophy department at Dartmouth, where she also teaches in the women's and gender studies program. The chat, scheduled for 5:30 pm at AS220, 115 Empire Street, is free and open to the public. The Phoenix caught up with Brison for a Q&A, via email, in advance of her appearance. The interview is edited and condensed.

GRISWOLD V. CONNECTICUT FOUND A RIGHT TO PRIVACY IN THE CONSTITUTION. CAN YOU PROVIDE A SENSE FOR THE LEGAL SIGNIFICANCE — THE LEGAL SWEEP — OF THAT FINDING? The significance of that finding was enormous. There is no mention of a "right to privacy" in the Constitution, but Justice William O. Douglas, writing for the majority, found that some rights not explicitly protected may nonetheless exist in the sense that "without those peripheral rights the specific rights would be less secure." The language Douglas used in Griswold to support the right to privacy was both broad and vague. He argued that "specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance." (The specific guarantees he referred to included the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments.)

That said, the right to privacy articulated and defended in Griswold was "the right to marital privacy," not a general right to privacy. It was not until 1972, in Eisenstadt v. Baird, that the Court established the right of unmarried couples to use contraceptives. In that case, Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., writing for the majority, held that "If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child."

In Roe v. Wade (1973), the right to privacy was found "broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy." [But] in Harris v. McRae, the Court decided that the right to privacy did not require the government to fund (through Medicaid) medically necessary abortions (even though Medicaid covered pregnancy and childbirth). In this case, Griswold was construed as protecting decisional privacy. The Court ruled that "although the government may not place obstacles in the path of a woman's exercise of her freedom of choice, it need not remove those not of its own creation."

Feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon has argued that the court's doctrinal choice to pursue the right to abortion under privacy law, rather than under equal protection law, was a mistake, one reinforcing a public/private split that has pernicious consequences for women.