THE DOC “I make no assumptions about who you are,” Forcier says. |

Dr. Michelle Forcier can't remember his name. But she remembers his face: a boy, 14, trapped in a girl's body. He was anguished. Hated what he was becoming.

"This kid," says Dr. Forcier, "just wanted to be himself."

She could suppress his period — that regular, bloody betrayal of his core identity; a birth control shot would do the trick. But she had little else to offer.

The physician felt she had failed her patient.

Dr. Forcier was running a clinic in Raleigh, North Carolina at the time. It was 1998. Before medicine really knew what to do with these kids. Before the Internet connected doctors to emerging protocols — and frightened teenagers to one another.

Fourteen years later, everything has changed.

Dr. Forcier is in Providence, now, at a Hasbro Children's Hospital clinic. And she is better equipped. On the leading edge, in fact, of a revolution in care for the young and transgendered.

She is delaying puberty for 11- and 12-year-old patients terrified of what's to come. She's administering estrogen to help teenage boys grow breasts and testosterone to help teenage girls deepen their voices. And she's sending young adults off to sex reassignment surgery.

Doctors in Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and a half-dozen other American cities are doing similar work. And for the first time, Forcier says, she can imagine a generation of transgendered kids growing up with bodies that feel right. For the first time, she can imagine a generation escaping the horrors of self-hatred and self-mutilation and suicide.

It is a remarkable moment. And a complicated one.

THE GENDERBREAD PERSON

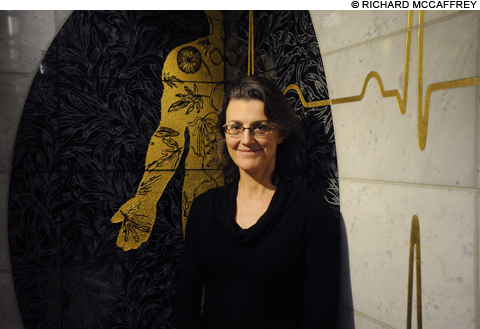

Dr. Forcier (pronounced FOR-see-ay) — thin, energetic, 47 — stands before a room of about 20 Brown University medical students in a modern, mid-sized classroom in the heart of Providence's Jewelry District.

Up on the screen: a rounded, cookie-like figure labeled "The Genderbread Person" — each part of its body symbolizing a different component of gender.

There is the crotch area — that's biological sex. The heart stands in for sexual orientation — that's who we're attracted to. Gender expression — our clothing, our speech, our mannerisms — is symbolized by the whole body. And finally, there is gender identity, found in the brain: our innate sense of maleness or femaleness.

In most cases, Forcier notes, our brains — our largest sex organs, she says — line up with our biological sex. But that's not always the case.

No one is quite sure how to explain the mismatch, formally known as "gender identity disorder" (GID) — a term losing favor among doctors like Forcier loathe to pathologize their patients.

Prenatal exposure to male sex hormones, like testosterone, may predispose some girls to male gender identity.

Genetics might play a role, too. A Dutch study of twins, conducted in 2006, suggested that genes could explain some 70 percent of atypical gender behavior. But it's unclear what, precisely, is passed from parent to child.

Transgenderism, whatever its root, has a long history. And some cultures have found a place for it. Native American tradition speaks of "two-spirits" who worked as healers, seers, and nurses. In Samoa, men who take on feminine gestures are recognized as fa'afafine, a third sex.