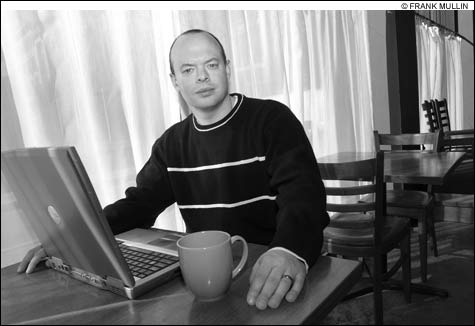

WEB POWER: Lee touts the Internet’s potential to expose political chicanery and to register young voters through text messaging. |

Bringing it all back home

While national groups have used the Internet to organize local events and meet ups across the country, Jo Lee, the Providence high-tech public relations consultant, has tapped the Web for smaller local campaigns.

When she returned to the US in 2001, after two years in South Africa, she was shocked by the shift in the political landscape. “When I came back there was the war, there was the economy, and it was a very depressing situation,” Lee says. “But I started getting these e-mails from MoveOn — ‘Click here to tell your Senator to vote against the war,’ and it was incredibly empowering. I was never the type of person who would go and write a letter. But I’ll click.”

In 2002, Lee became involved with the Summit Neighborhood Association in Providence, which was protesting Miriam Hospital’s proposed expansion. Inspired by an Arianna Huffington column on civic engagement, and her own community involvement, Lee decided to take things to another level.

With the help of her brother-in-law, a computer programmer, she put together CitizenSpeak,a Web site where people can design their own free MoveOn-like e-mail campaigns, targeted at a specific politician or decision-maker.

Lee sees great potential in the Internet as an effective advocacy tool in local campaigns, particularly since national politicians receive a lot more e-mail.

A case in point is the Rhode Island Coalition Against Domestic Violence’s (RICADV) effort to pass a protective order gun ban in 2003. After holding a State House rally and using CitizenSpeak to send more than 200 e-mails, legislators began soliciting meetings with the coalition.

“Legislators were amazed by the flood of e-mails they were receiving,” Patricia Loomis, who RICADV’s senior policy associate at the time, says in an interview on CitizenSpeak’s Web site. “At the local level, legislators simply aren’t used to hearing from such large numbers of constituents. It definitely played a role in winning the support of the Senate president, [Joseph Montalbano,] who cares what constituents think.”

Wiki politics gets personal

One of the most tech-savvy individuals to try his hand at politics last year was Pete Ashdown, an Internet service provider founder-turned-US Senate candidate in Utah.

Ashdown, who ran as a Democratic challenger to Orrin Hatch, focused his campaign on citizen participation through new technology. When Ashdown began, he put up 12 policy positions on his Web site. Using wiki technology, the site allowed users to add to or edit his ideas — something that led him to embrace 50 policy positions, ranging from “Abortion” to “Wiki,” with input from 100 people.

What he heard most in his travel, Ashdown says, was that Utahans felt disconnected from Washington, and that the wiki served as a way to take their views into account.

The candidate’s Iraq stance, for example — that the US should ask Iraqis if they want us to stay or leave, and then do that — was suggested by an anonymous American on his wiki. Ashdown was surprised how the idea resonated with liberals and conservatives in Utah, but says, “That’s what I think is key to good public policy; it’s finding a compromise that people can move forward on.”

Ashdown also posted his schedule online, along with campaign ideas. When he put up a campaign commercial on his Web site — a cute spot featuring his toddler daughter waving American flags to a campaign jingle — one campaign volunteer thought he could do better. In the volunteer’s ad, an “Ashdown Action Figure” shoots his “transparency rocket” to expose the bad guys’ backroom deals, a commercial that the candidate then used in his campaign.

Though Ashdown lost his race, attracting 30 percent of the vote, he plans to run again, and hopes that his ideas inspire other politicians. Among those already following his lead is Steve Urquhart, Republican Rules Committee chair in the Utah House of Representatives.

On January 22, Urquhart launched the wiki site Politicopia to discuss the state’s legislative issues. Urquhart wants the site to “improve people’s access to information in my state . . . provid[ing] a quick and solid handle on the process — without the intermediaries filter,” he writes on Personal Democracy Forum.

While it remains to be seen if such efforts attract participation beyond just a relatively small group of people, Personal Democracy’s editors call Urquhart’s site — said to be the first time that an elected official has created a political wiki — “a sea change in the relationship between representatives and voters.”

HARD-WIRED: Thanks to the ’net, blogger-activist Crowley was able to link up with other supporters of Barack Obama. |

Looking back and ahead

On a weekend in December, about 400 progressive political organizers, activists, techies, and bloggers squeezed into a conference room in Washington, DC.

Despite the tech-savvy nature of the participants (including Lane Hudson; Chris Casey, credited with having created the first congressional Web site in 1994; and Eli Pariser, who started the precursor to www.moveon.org in 2001), the event included some markedly low-tech elements.

This two-day RootsCamp election debriefing took its cue from online open-source technology that promotes user participation. Instead of sessions planned in advance, any participant could hold a workshop by putting a sign up on the wall. It was a chance for the techies, activists, organizers, and online fundraisers who worked on the 2006 election to talk about what worked — and what didn’t — as they prepared for the 2008 campaign season.

Back in Rhode Island, blogger-activists like Pat Crowley, 33, assistant executive director of the National Education Association-Rhode Island, hope to bring a more ‘active’ element to online organizing: It’s no longer just “putting up the information online,” he says. It’s “Here’s the information, now do something with it. It’s active in the sense that it’s not afraid to tell people, ‘Here’s what I want you to do. You read about the minimum wage — now send a message to this company that’s paying their workers under the minimum wage.’ ”

Most recently, Crowley jumped on the Barack Obama bandwagon. While just seven people showed up for December 7 pre-meeting, six were strangers who “I probably never would have met” without e-mail and the Draft Obama Web site he established. “That organic element is fun,” Crowley says. “How to take it from there to a real organized campaign — that’s going to be the test, to see if this Internet-based way of doing things works.”

The most technically innovative Rhode Island candidate in 2006 was probably Frank Caprio, now the state’s general treasurer, who used Cox Communications’ On Demand feature for an extended campaign commercial and even created his own Internet TV station.

“We realized we needed to make it more interesting if people were going to pay attention to the treasurer’s race,” says Xaykham Khamsyvora¬vong, Caprio’s campaign manager. Caprio used his Internet TV channel, for example, to discuss his plans for the state pension fund and for divesting the state from Sudan.

While he faced negligible opposition and is a potential gubernatorial candidate in 2010, Caprio used technology to show how he would make government more effective, says Khamsyvoravong, and made “early and bold moves” with technology that may have discouraged others from entering the race.

What’s next for the roots?

With the 2006 election barely passed, the 2008 frenzy is already beginning, and hopes for technology’s role are high.

“The 2008 election will produce the ultimate democratization of information technology,” says Brown University political science professor Darrell West. “You’re going to see everyone have the potential to become a journalist, and to record information that might have consequences for the election.”

It will likely take years before we can fully understand what’s happening at this moment.

“I think it’s too early to try and quantify this technology’s impact,” says Joshua Levy, associate editor of Personal Democracy Forum. “But think of it like the 1960 first televised presidential debate — we saw Nixon sweating, we saw how handsome JFK was, and that decided the election. We [will] look back and see this as a turning point in the way political campaigns are run.”

And changes happen fast: YouTube, for example, is less than a year-and-a-half old. “We can’t be certain this [wave of new technology] will change everything,” Levy says. “But we can be certain that [in] 2008 there will be something new and big that we don’t even know about yet.”Email the author

Erica Sagrans: ericas@gmail.com

Topics

Topics:

News Features

, Mitt Romney, Barack Obama, Social Software and Tagging, More  , Mitt Romney, Barack Obama, Social Software and Tagging, Evan Bayh, Mark Foley, Brown University, National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, Frank Caprio, Jo Lee, Pat Crowley, Less

, Mitt Romney, Barack Obama, Social Software and Tagging, Evan Bayh, Mark Foley, Brown University, National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, Frank Caprio, Jo Lee, Pat Crowley, Less