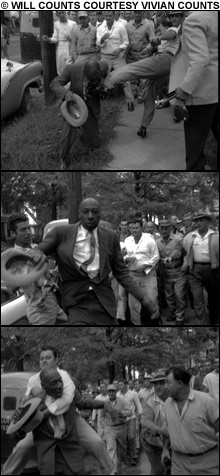

PICTURE OF DIGNITY: Black journalists covering the civil-rights movement couldn’t expect police protection. Here Tri-State Defender editor L. Alex Wilson is attacked by a Little Rock mob: he’s kicked, he rises, and then he is attacked from behind. |

Strictly speaking, the new book by journalists Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff — The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation (Knopf) — is a chronicle of civil-rights-era reportage. But this description doesn’t do it justice. The book is, at the same time, a protracted inquiry into the purposes of journalism, a probing social and cultural history, and a meditation on the value of “objectivity.”That The Race Beat works on so many levels — and reads like a novel, despite being laden with facts — testifies to the talents and pedigrees of its authors. Klibanoff, who’s currently the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s managing editor for news, spent two decades at the Philadelphia Inquirer, including stints as the paper’s national correspondent and deputy managing editor. (He also worked for the Globe for three years.) About half of Klibanoff’s Inquirer tenure, in turn, came when Roberts was the paper’s executive editor. This was a golden age for the Inquirer: during Roberts’s 18 years atop the masthead, the paper won a remarkable 17 Pulitzer Prizes.

Earlier in his career, in the mid 1960s, Roberts had covered the race beat for the Times; he rejoined the paper as managing editor in 1994, and is now a professor of journalism at the University of Maryland, College Park. Last week, Roberts spoke to the Phoenix from his home in New York about The Race Beat and its implications for journalism today. An edited transcript follows.

Let’s start with a question that seems both very important and very obvious: what lesson does The Race Beat hold for today’s press?

I think it tells us that when the press decides and makes a commitment to cover important news, it can do it successfully. But it takes commitment.

I had the impression that you and Hank Klibanoff were drawing an even bigger lesson from this — namely, that major social change won’t happen unless the media forces people to pay attention.

Right. That is one of our major points.

Given the business exigencies of journalism today, could the press’s commitment to civil rights be replicated? You describe the New York Times being hit with multiple libel suits, and the Arkansas Gazette — which offered moderate or progressive coverage — experiencing a serious drop in circulation and revenue. Plus, there’s an emphasis on giving people the news they want. I don’t know how many people would want to be exposed to a story like this if they were given a choice.

I think that’s true. I’ve thought a lot about the difference between the press today and the press in the ’50s and ’60s, and there are good sides and bad sides to it. I think today, because you have chain ownership and group ownership, you wouldn’t have the rabidly segregationist papers that you had in the ’50s. I also don’t think you would have a Ralph McGill or a Harry Ashmore today. [McGill edited and later published the Atlanta Constitution; Ashmore edited the Arkansas Gazette.]