From being physically harassed in my middle-class catholic high school in the mid 1960s to being assaulted in boston’s outdoor cruising areas, i’ve seen a lot of anti-gay violence up close. The closest i’ve come to deadly violence was on November 18, 1980. I had been standing in front of the Ramrod bar in New York’s Greenwich Village, as several dozen men in leather jackets and jeans were chatting and cruising, taking a break from the small, always smoky bar. Soon, I left for the Mineshaft, another west village club, noted for its rowdy thursday two-for-one night. Thirty minutes later, Ronald K. Crumpley fired 40 rounds from a semiautomatic rifle and two pistols into the cluster of men i’d been standing with in front of the ramrod, killing two and wounding six others. Bartenders at the Mineshaft quietly told us what had happened and urged us to be careful, since no one was certain there was only one shooter. In the ’60s and ’70s, public expressions of homosexuality and physical violence were so intricately bound together that, as a community, we simply expected it. In this part of the world, in 2006, things have indeed changed for gay men. That is why the attacks at puzzles lounge in new bedford were truly shocking.

From being physically harassed in my middle-class catholic high school in the mid 1960s to being assaulted in boston’s outdoor cruising areas, i’ve seen a lot of anti-gay violence up close. The closest i’ve come to deadly violence was on November 18, 1980. I had been standing in front of the Ramrod bar in New York’s Greenwich Village, as several dozen men in leather jackets and jeans were chatting and cruising, taking a break from the small, always smoky bar. Soon, I left for the Mineshaft, another west village club, noted for its rowdy thursday two-for-one night. Thirty minutes later, Ronald K. Crumpley fired 40 rounds from a semiautomatic rifle and two pistols into the cluster of men i’d been standing with in front of the ramrod, killing two and wounding six others. Bartenders at the Mineshaft quietly told us what had happened and urged us to be careful, since no one was certain there was only one shooter. In the ’60s and ’70s, public expressions of homosexuality and physical violence were so intricately bound together that, as a community, we simply expected it. In this part of the world, in 2006, things have indeed changed for gay men. That is why the attacks at puzzles lounge in new bedford were truly shocking.

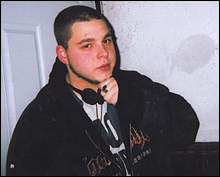

Last Thursday, just after midnight, Jacob D. Robida, an 18-year-old high-school dropout, entered Puzzles Lounge, and after being served two drinks asked if it was “a gay bar.” When told that it was, he assaulted patrons with a handgun and a hatchet, wounding three men, two seriously. He fled home, left a note for his mother that apologized and expressed his love, but added, “I have to go out by my means.” He then took her car and left, picked up his ex-girlfriend Jennifer Bailey in West Virginia, and drove to Arkansas, where he shot and killed a part-time police officer. After a 16-mile chase, Robida crashed his car and then shot Bailey in the head, before he shot himself as he was beset by state troopers and police. He died the following day. According to news reports, when New Bedford police searched Robida’s bedroom they found “homemade posters disparaging African-Americans and Jews; neo-Nazi literature and skinhead paraphernalia,” as well as an empty coffin.

The first response to the attacks, by the police, the media, and spokespeople for gay groups, was that this was a “hate crime” — that is, a crime that specifically targeted homosexuals. Although Bristol District Attorney Paul F. Walsh Jr. has stated that Robida seemed to have no connections to any known groups that promoted an anti-Semitic, racist, or anti-gay ideology, filling one’s bedroom with Nazi regalia suggests at least a serious predisposition to social malignity.