Other cities built on filled land, such as Milwaukee, St. Louis, and St. Paul, eventually solved the problem through “urban renewal” — tearing down the old neighborhoods and rebuilding. Boston did the same on a small scale in the 1980s, when a group of Chinatown homes was deemed too damaged by depleted groundwater to repair.

Eventually, that is exactly what will happen to Boston if the groundwater levels aren’t cared for with constant vigilance — and fast. Imagine the Back Bay rebuilt, without the rounded brick bays laid by Victorian-era craftsmen. Imagine the North End rebuilt without any trace of Paul Revere.

In other words, imagine Boston turning into just another city.

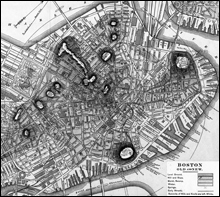

STAYING AFLOAT: Much of the city’s prized real estate sits on man-made land. If groundwater levels fall, a wealth of 19th-century architecture falls with it. |

Years of governmental neglect

For years, both city and state government abdicated their responsibility to monitor, regulate, and protect Boston’s groundwater levels. Finally, in the past 18 months or so, Menino and various local and state agencies — the BRA, the MBTA, the Boston Water and Sewer Commission, the MWRA, and the state’s Office of Environmental and Energy Affairs — have stepped up to form a non-binding agreement to address the issue through a City-State Groundwater Working Group. In a rare display of mutual amity and cooperation, they have done a fine job of beginning to address the problem.During that time, since the city finished installing a network of monitoring wells, we have seen stark evidence of how groundwater levels change constantly, throughout the city, due to localized problems that are difficult to detect and often costly to repair.

For example, wells in East Boston revealed unexpected groundwater-level problems that were eventually traced to leaks in Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) sewer lines, which the agency is now fixing. In the South End, a previously disinterested MBTA was convinced that leaks at Back Bay Station were rapidly depleting the groundwater; it is now working to fix them, and will eventually install a groundwater-replenishing system.

Just last month, the Boston Groundwater Trust found that “a significant drop” in groundwater levels along Congress Street at Fort Point Channel was due to a nearby development project pumping more than three million gallons out of the ground since January — and was permitted to do so.

Such problems had gone undetected and unaddressed through years of almost total governmental neglect, even though a 1983 law required the DEP to regulate low-lying “tidelands,” including most of Boston, and parts of several outlying towns.

That work was neglected because in 1990 the DEP looked at its tiny staff and the thousands of acres of tidelands, and decided to make things easier by simply excusing itself from the vast majority of its obligations.

The agency issued a regulation exempting all “landlocked filled tidelands” from the new law, defined so expansively that some 4000 acres — 3000 in Boston alone — were freed from DEP oversight. For the next 17 years, the state turned a blind eye to development on those exempted lands, until the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) ruled this February that the state had no right to rewrite the law as it did.