What exactly is in these books? To a lay reader — especially an American who takes regular, peaceful political change for granted — the contents might seem utterly unobjectionable, and maybe even a tad dry. Here’s a sample passage from Waging Nonviolent Struggle: 20th Century Practice and 21st Century Potential:

The act of protest may be intended primarily to influence the opponents — by arousing attention and publicity for an issue, with a hope to convince them to accept a proposed change. Or, the protest may be intended to warn the opponents of the depth or extent of feeling on an issue, which may lead to more severe action if a change the protesters want is not made. Or, the action may be intended primarily to influence the grievance group — the persons directly affected by the issue — to induce them to take action themselves, such as participating in a strike or an economic boycott.

Zesty it ain’t. But Sharp isn’t a prose stylist — he’s a social scientist who’s anatomizing his chosen subject in meticulous detail. What’s more, he’s not writing for a general readership. His audience is anyone who seriously wants to bring down a government. His writings, in essence, are strategy manuals that explain how to achieve this goal. And those who know his work say his influence is enormous.

“He’s a giant in the field,” says David Cortright, the president of the Fourth Freedom Forum and a research fellow at Notre Dame’s Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. “He’s the world’s leading scholar on nonviolent action as a means of political change. And his reputation is so commanding, and his work is so established, that you can’t even begin to work in this field without acknowledging and working from his foundation.”

Stephen Zunes, a professor of political science at the University of San Francisco and principal editor of the anthology Nonviolent Social Movements, puts it this way: “He’s really the person who laid out the framework for understanding strategic nonviolence and how it works. A lot of activists have used that knowledge base that he’s put together to organize and mobilize their movements. All of us who study in this field owe him a huge debt.”

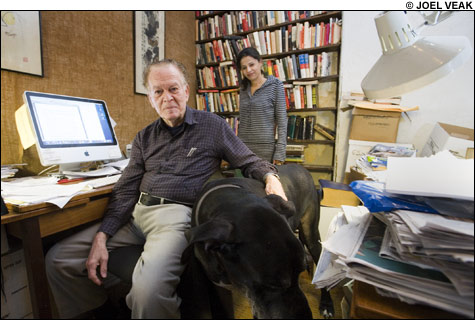

RADICAL ZELIG: Gene Sharp (seen here at home with Albert Einstein Institution Executive Director Jamila Raqib and his Great Dane, Caesar) is attached to political rumblings in Venezuela, China, Serbia, Iraq, Ukraine, and the Baltics, among others. |

Intellectual propriety

According to Ivan Marović — a former leader of Otpor, the group that brought down Milošević after passing around copies of From Dictatorship to Democracy — Sharp is a great synthesizer rather than a groundbreaking thinker. “If you read [French political philosopher] Etienne de la Boetie, it’s 16th-century discourse; if you read David Hume, you have to find his thoughts on nonviolence among many other themes,” says Marović. “But Gene Sharp is focused only on this. He wasn’t inspirational, because we’d already been using nonviolent resistance for some time. But to find what we were doing written in a book, with everything put in one place, was very valuable.”