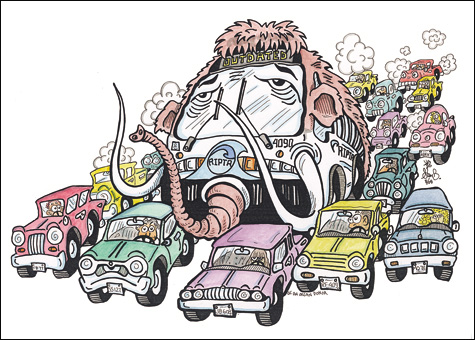

AUTO ASPHYXIATION: Rhode Islanders have been car-dependent for so long that other approaches

get short shrift. |

Jennifer Bulpitt, 16, who lives on the East Side, uses RIPTA to get to school, to her job, to her friends’ houses — just about everywhere she wants to go. But because of recent state welfare cuts, she can ride the bus only 10 days a month, instead of every day.

“I can’t go to school [just] 10 days out of the month,” says Bulpitt, who will start the 12th grade at Central High later this month. She lives almost three miles from the school — too far to walk, but just under the distance requirement that would entitle her to transportation through the Providence schools.

Bulpitt is one of thousands of Rhode Islanders who rely on the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority to get where they need to go. But it’s not just the relatively small number of RIPTA users who suffer from the inadequacy of Rhode Island’s transit system.

For starters, rising gas prices have made the car — that great American icon of freedom and mobility — more of an albatross than a mode of transit. Even with the per-gallon cost dropping below $4, filling up a relatively fuel-efficient car can still chew through $50 or $60. And higher gas prices seem likely to remain a reality for years to come.

Our traditional reliance on the car is also taking a toll on the environment. More than a third of greenhouse gas emissions in Rhode Island, for example, are caused by the transportation sector, most of it from cars and trucks. And sprawling development, made possible by the rise of the automobile, costs the state more money, threatens Rhode Island’s traditional character, and has left thousands of lots vacant in the state’s five core cities.

To make matters worse, Rhode Island’s transportation infrastructure is literally falling apart, with weight restrictions having been placed on at least two major bridges, includ-ing one on Interstate 95 in Pawtucket.

Public transit advocates point to the Ocean State’s small size in touting its potential to become a place with a cooler and more effective approach to transit, encompassing light rail, faster bus service, and other innovations.

Scott Wolf, executive director of the advocacy group Grow Smart Rhode Island, calls public transportation “the major missing ingredient in making Rhode Island a smart growth leader. Denser “smart growth” development, he says, in which people work and shop closer to home — a familiar pattern for some Providence residents — could improve air quality, cut com-muting time, and stimulate economic growth.

For now, though, the state’s inability to move forward is symbolized by how funding is waning for perennially cash-strapped RIPTA — when its service is needed more than ever — since it is funded through the gas tax. And with the state facing a continued budget crisis, any significant changes remain a long way off.

Portland has a better way

Barriers to better transit, like the federal focus on funding highway work and the American emphasis on car ownership, are at play everywhere. Yet some cities have managed to overcome these barriers.

Portland, Oregon, is at the forefront of a growing number of communities moving to integrate dense, economic development with green and easily accessible public transit.