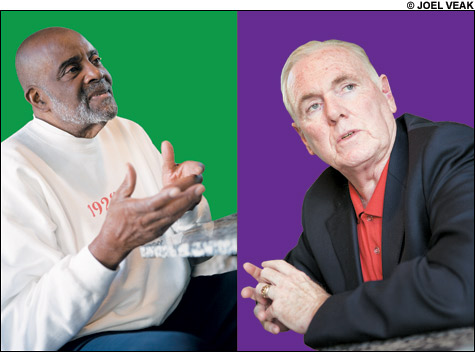

OLD RIVALS: Mel King (left) and Ray Flynn (right) had more in common than voters acknowledged. Today, they can look back on their role as a joint accomplishment. |

Barack Obama's presidential candidacy was a seminal event in American race relations. To be sure, racism still exists. But the distance our culture has come in 50 years — from blacks fighting for basic civil rights to a black man running for the White House — is remarkable.

Twenty-five years ago, Boston had its own politico-racial catharsis. In 1983, a mayoral battle pitting black against white seemed like the last thing Boston needed, but that's what it got. Following Judge Arthur Garrity's 1974 court order to integrate Boston's public schools, the city teetered on the brink of all-out race war for years. In truth, few people liked the busing solution or the logistical disruptions that came with it, but anti-busing sentiment quickly turned so ugly — epitomized by the infamous 1976 attack on black lawyer Ted Landsmark by a flag-wielding protester — that most African-Americans and liberals felt compelled to defend Garrity's ruling.

By the time four-term incumbent mayor Kevin White decided not to seek re-election, the tension surrounding busing had been toned down, but the issue remained on everybody's mind. That year's mayoral contest — between candidates too easily adopted as symbols of the warring community factions — could have pushed simmering racial antagonisms over the edge. Ray Flynn, a populist from South Boston, the epicenter of anti-busing sentiment and working-class Irish anger, who'd once publicly opposed busing, faced Mel King, the imposing, charismatic, African-American progressive from the South End.

In the end, though, the potentially volatile contest proved to be a good thing. To say it healed race relations in Boston would be an overstatement. It did, however, facilitate the healing process. Flynn and King had their differences, but they also had significant affinities, including an intense interest in public education and a penchant for grassroots politicking. And rather than playing dirty — or getting incendiary — they waged a professional, mutually respectful campaign.

These things alone would make the '83 mayor's race noteworthy. But factor in the slate of high-power candidates — including Boston City Council President Larry DiCara and former Boston School Committee president David Finnegan — whose names appeared on the preliminary election ballot, and the huge level of public participation (nearly 70 percent of Boston voters came to the polls on Election Day that year, the most since 1949), and a strong case can be made that that election marked a high point in Boston's storied political history.

Recently the Phoenix spoke with Flynn (who won the election and served as mayor until 1993, remaking Boston's school-governance structure in the process, before becoming ambassador to the Vatican) and King (who ran for Congress in 1986, then turned decisively from electoral politics to community activism after the election) about the race, its effect on Boston, and what's changed — and remained the same — in the intervening years, as Boston has gone from a city that's two-thirds white to one in which whites and "minorities" are equally populous. An edited transcript follows; for more of the King-Flynn Q-&-A, go to thePhoenix.com.