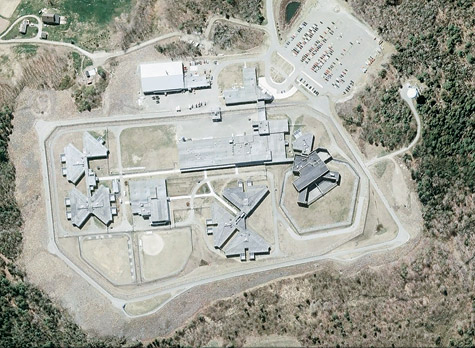

VIEW FROM ABOVE The Maine State Prison, via satellite. |

Many other tortures

Other torturous conditions exist in the supermax. Another name for supermax is “control unit,” and guards aggressively try to control a prisoner’s every action. If an inmate protesting bad food covers up the small window to his cell, for example, a Swat-like team of helmeted guards charges into it. The point man knocks the inmate flat with a shield and others spray Mace on him and shackle him hand and foot. The guards then carry him to a room where he is strapped into a restraint chair, in which he may sit moaning for hours. These beatings are known as cell extractions. (Parts of one can be seen at thePhoenix.com/AboutTown in a prison video leaked to me.) Former prison chaplain Moody says, “Prison guards by nature — even the good ones — have little patience for mental illness. They view it as weakness.” In my articles I have portrayed Michael James, a severely mentally ill young man serving time for theft who suffered up to five extractions a day.

James also threw his feces at guards. In such a case the prison’s routine is to charge the perpetrator with felony assault, each charge potentially adding five years to a prisoner’s stay — a kind of legal torture of the mentally ill. At one point James accumulated 10 assault charges, for which he went on trial. But after a heroic effort by his attorneys, James was committed to the state’s mental hospital in Augusta. Recently James told me that, because he suffers from “silent seizures,” doctors think he may have something organically wrong with his brain, and they are scheduling him for a CAT scan. So he may have suffered the state’s wrathful torture for years because of a physical brain defect.

The most common legal torture is the lack of due process a prisoner experiences when he’s placed in the supermax. Among other deprivations, supermax placement means a loss of education, other rehabilitation activities, a prison job, religious services, and “good time.” Because of a 1990s federal law curtailing their right to bring a suit, inmates are rarely successful in challenging prison decisions. In addition, what a prisoner has to do to get out of the supermax is usually not revealed to him.

There is little mental health care in the supermax despite the enormous need. Sam Caison says it’s mostly “five to ten minutes a week with a mental health worker, usually outside the door.” Solitary confinement is well documented to lead to a breakdown of physical health, but the medical care given Maine’s prison inmates, especially those in the supermax, is notorious. After a sickly inmate, Sheldon Weinstein, died in the supermax last April following a beating by inmates while he was in the prison's general population, his widow instituted a $1-million-plus lawsuit against the prison, claiming “the medical staff did nothing in the face of obvious injury,” her lawyer said.

In November another sickly inmate, Victor Valdez, was roughly hauled off to the supermax, prisoners say, for not immediately following an order, which he may not have understood because his English was poor. He died not long afterward in unexplained circumstances. The state police are investigating both deaths.

Even dental care amounts to low-level torture. Supermax prisoners are not allowed toothbrushes, but must use a ribbed plastic nub that fits over a fingertip. They say it’s inadequate.

A regular sexual humiliation is the “butt search” for drugs despite the prisoner’s solitary confinement. Says former inmate Tino Marino, “When you go out to the cage for exercise, they make you strip down and lift your balls. Some guards do that because they like that.” Marino’s lawsuit alleges an officer forced him to grab his genitals through his pants and walk through a cellblock in front of other inmates and a female guard.

Completely counterproductive

Extensive supermax systems don’t exist outside the United States not only because the American attitude toward lawbreakers is exceptional — we have 4.5 percent of the world’s population and almost 25 percent of its prisoners resulting from an incarceration rate more than five times the world average — but also because of the expense. Since supermax buildings are so high-tech and the management of their prisoners is so labor-intensive, supermaxes “typically are two to three times more costly to build and operate than other types of prisons,” Florida State criminologist Daniel Mears writes.

One might ask, then, why these expensive monsters were built — they now contain, according to Mears, at least 25,000 inmates in 44 states. Scholars agree they were part of the “tough on crime” mania and the resulting prisoner-population explosion that swept the nation beginning about the time of Ronald Reagan’s election as president in 1980. Supermaxes are “the animal of public-policy makers,” federal National Institute of Corrections official George Keiser told me. The animal was fed by politicians capitalizing on public fears incited by increasing news-media sensationalism in covering crime.

A kind of “fad,” as Keiser called supermaxes, they were built without knowledge they would accomplish what their supporters said they would: reduce prison violence by separating out aggressive inmates and by deterring inmates from violence. Indeed, there’s “no empirical evidence to support the notion that supermax prisons are effective” in reducing prison violence, says a comprehensive study published in The Prison Journal in 2008.

“Supermax prisons are expensive, ineffective, and they drive people mad,” says Sharon Shalev, of the London School of Economics, author of a new scholarly book, Supermax: Controlling Risk Through Solitary Confinement. “This place is a breeding ground for hate, pain, violence, and failure,” writes current Maine supermax resident Jacob McInnis Sr. All evidence indicates that supermaxes are, in terms of benefits to society, completely counterproductive.

When the enraged and mentally damaged inmates go back into the prison general population or the outside world, as the vast majority do, Kupers, the psychiatrist, writes, “We are seeing a new population of prisoners who, on account of lengthy stints in isolation units, are not well prepared to return to a social milieu.” In the worst cases, supermax alumni — frequently released from solitary confinement directly onto the street — “may be time bombs waiting to explode,” writes criminologist Hans Toch. But Michael Woodbury and Sam Caison demonstrate that the time bombs are already going off.

The worst effect of the supermax, though, may be moral. If there is torture, then there are torturers. Says Maine Civil Liberties Union executive director Shenna Bellows, “By dehumanizing prisoners, we dehumanize ourselves.”