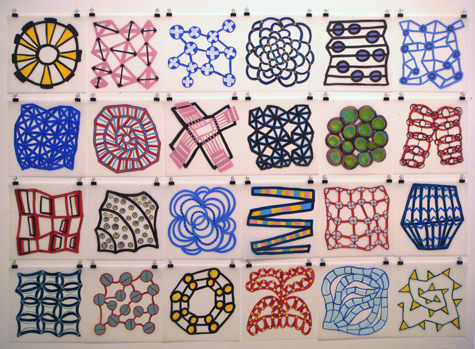

“ALL TOGETHER NOW,” Acrylic on Duralar, 10x16 feet, by Cassie Jones, 2010. |

The Center for Maine Contemporary Art is back in full swing after an unexpected winter hiatus. The opening of the center’s Biennial this weekend was celebratory, the cars that lined the lengths of the sleepy Rockport streets evidence of the community’s support. The whitewashed galleries are now crowded with works by 41 artists who bear various connections to Maine, culled from a daunting pool of 654 applicants by jurors George Adams of George Adams Gallery in New York, Boston-based independent curator Rachael Arauz, and Belfast landscape painter Dennis Pinette.

While aiming to present both the resilience of a Maine artistic tradition and Maine’s contribution to the larger contemporary scene, the exhibit is heavy on the former, with landscape paintings and photography running rampant and a curious absence of video, sound, and new media. Many of the landscapes are beautifully rendered — Susan A. Cooney’s miniature graphite islands are impeccable, and Ken Sahr’s bleak portraits of Seal Harbor cool and nostalgic — but as a force here they are underwhelming.

Where the success lies in this pairing of the traditional and the progressive is the confrontation and integration of the two. Several artists act as ambassadors here. Carrie Dickason’s “Untitled (Garden)” addresses the assimilation of the unnatural and synthetic into our landscapes with her cinder-block raised-bed installation in the gallery, in which a mish-mash of living grass, shag rug, and de-threaded oriental carpet are interwoven. Kenneth Deprez’s “Through the Body” layers pencil and acrylic on mirrored photographs of roller coaster scaffolding, reminiscent of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photographs of industrial architecture. Blocks of transparent color are Tetris-ed over the image, and red lines harshly dissect the work, giving the overall effect of a hazy and questionable memory of a place. John Lorence’s abstracted oils on canvas feed mountainous horizons through refracted shards, with muted earth tones and fleshy pinks framed by assertive black lines, both graphic and expressive.

Rangeley couple Shannon Rankin and Justin Richel provided two of the strongest works in the show, both with large-scale installations nicely occupying their own brand of witty elegance. Rankin, who was awarded the Juror’s Prize, pushes her topographic metaphors into three-dimensional space with “Falls,” a graceful and exacting pyramid of cascading parabolas snipped from the baby blue oceans in maps. Jurors lauded her “rare zone of originality” and her “language of abstraction clearly defined.” Richel’s “Whirling Dervish” introduces the upstairs gallery with a 10-foot-tall wispy tornado of his trademark candy-colored pastries, ewers, modern and Victorian furniture all spilled from a bright blue coffee cup. Each object in Richel’s Carroll-inspired tea-party-gone-disaster is painstakingly rendered in gouache and cut from paper, delectably and eerily perfect in perspective and detail.

Cassie Jones parallels Richel in the gallery, with a wall-size grid comprised of 72 bold and whimsical works on paper. Each piece contains a brightly hued seed-like form, seemingly plucked from a constellation of like forms. The works within the grid reflect one another but are never repetitive, suggesting something molecular, something mechanical, but mostly something playful. Squirreled away beside Jones’s work in the gallery, and unfortunately trumped by the grid only because of their subtlety, are Bridget Spaeth’s gorgeous wood-panel sculptures: confidently minimal architectural elements protruding in quiet arcs from the wall.