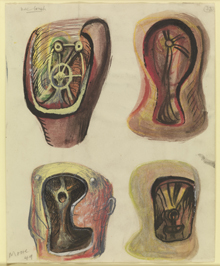

“HELMET HEADS” Pencil, chalk, charcoal, wax crayon, watercolor, ink and gouache, by Henry Moore, 1949. Credit: Henry Moore Family Collection and Hauser & Wirth, reproduced by permission of The Henry Moore Foundation. |

Widely considered to be one of the most influential sculptors in the formation of British and international modernism, Henry Moore (1898-1986) drew from classical traditions, surrealism, and primitivism in his obsession with capturing the female form in all of its dimensions. In a new exhibit at Bowdoin College Museum of Art, the scope of Moore's manifestations of the figure can be viewed through a robust survey of 48 works on paper spanning six decades of the artist's productivity. Beginning with brisk academic life-drawings from the mid 1920s and concluding with harsh reductive black silhouettes from the early 1970s, Moore's garnered influences and dictating circumstances can be traced through the chronologically sound collection of drawings that both supplemented and bolstered his three-dimensional work.

Moore's drawings were both auxiliary to his sculpture and autonomous from it, serving as studies and blueprints as well as existing as independent completed works. Moore struggled and played with this dichotomy in status; many of the drawings featured in the exhibit are titled as ideas or sketches for sculptures, but hold their own weight as stand-alone works. Paired in the gallery, his 1937 "Ideas for Sculpture" and 1944 "Sketches for Sculpture" exemplify the artist's seeming inability to let preliminary drawings exist as just so. "Ideas for Sculpture," a pencil and wax crayon on paper, illustrates what could be the artist's process of distilling figures to his signature biomorphic forms. Five small scenes line the top of the page, depicting abstracted figures in obscured scenarios of what read like conversing or love-making, each rendered in a rich and whimsical line and residing in a surreal expanse of space. The juxtaposition and grouping of the scenes suggests a narrative, or a film reel. Below the reel are four larger abstracted forms extracted from the drawings above, figural objects reduced to almost no discernable human form. Similarly, in "Sketches for Sculpture," a graphite and pen and ink wash on paper, nine separate figural and architectural forms are worked out on one ground, bathed in a deep wash that places them all on one moody plane.

Moore's drawings are sculptural in nature, with sharp definitions of form and heavy shading and highlights. His materials are treated on paper as they would be in three dimensions, with a strong physicality in his mark-making and application of a range of mediums. His handling of pencil, chalk, wax crayon, pen and ink, and watercolor (which are at times all used in the same work) is intuitive and visceral.

"Henry Moore — The Drawings" opts to hang works together that are related aesthetically or in theme but divided by decades as opposed to providing a straight timeline, highlighting the continuity of Moore's vocabulary throughout stylistic shifts, historical conditions, and cultural engrossment. His investigations of the reclining female figure in early student work are smartly juxtaposed with those created when he was preoccupied with pre-Columbian art or influenced by Picasso or de Chirico. The theme of mother and child is examined through un-abstracted life drawing and then filtered through a more conceptual lens in his 1932 "Studies of Lobster Claws" and 1949 "Helmet Heads," which he describes as explorations of protection, a hard shell covering soft flesh, as a parent protects a child. The effects of World War II are heavily measured in the exhibit, as Moore became a commissioned war artist, depicting scenes of Londoners sleeping in the underground for shelter. His "Shelter Drawings" are thus some of the most resolved in the exhibit.