CANON FODDER Five of David Goodis's novels — originally published as cheap paperback originals — have now been collected in a volume from the prestigious Library of America.

|

You know, some people got no choice

And they can't never find a voice

To talk with that they can even call their own

So the first thing that they see

That allows them the right to be

Why they follow it, you know, it's called bad luck.

_Lou Reed, "Street Hassle"

Because we live in a country that forever needs to be told to appreciate its native artists, Americans are in love with classification. Is this writer high or low? Are genre novels literature or entertainment? Which is why it's far more important for the critic to evoke than to classify, to let judgment arise from critical description and from what D.H. Lawrence called the account of a work's "effect on our sincere and vital emotions." That is the sort of judgment that understands both the importance of technique and why technique can be irrelevant, why uneven novels with purple passages or patches of slack narrative can be so affecting, and why the most immaculate literary precision can leave us cold. And it's that judgment that has to be applied to the work of David Goodis.

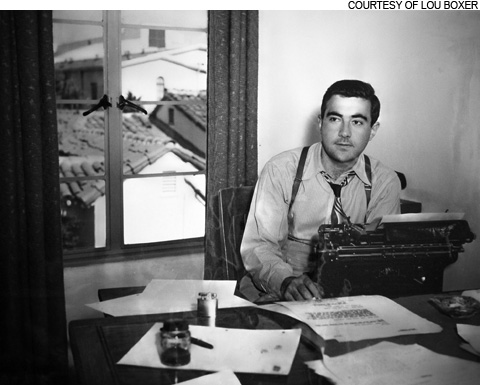

It's easy — too easy — to comment on the irony that Goodis (1917-1967), whose output from the '40s through the '50s came mostly in cheap paperback originals, is now receiving his own volume in the prestigious Library of America series. Embrace that irony and you're embracing the notion that the canon cannot make room for writers like Goodis. The implicit belief behind the existence of this volume, edited by Robert Polito — a fine poet and the biographer of another noir artist, Jim Thompson — is that good writing is good writing.

And yet, trying to explain Goodis to someone who has never read him, or even to talk about him with someone who has sunk into one after another of these hallucinatory works, the question keeps nagging at you: what the hell kind of writer was he?

"Crime writer" is the off-the-rack description used by most critics to describe Goodis, and it's true that a crime is at the center of all the books collected in Five Noir Novels of the 1940s & 50s. But the reader who turns to Goodis for the pleasure of watching a mystery solved or the mechanics of a police procedural may feel as if he's been cheated. To read Goodis is to slip into the most luxuriant of nightmares, to be trapped in a state of mind shared by the panic-stricken paranoid and the most masochistic of romantic fatalists. If you can imagine having an anxiety attack while slumped in your easy chair, sucking down cigarettes and whiskey and listening to Frank Sinatra sing "Deep in a Dream," you're close to imagining the experience of reading these novels.